Scalpel:

Etymology: < Latin scalpellum, scalpellus, diminutive of scalper, scalprum. Compare French scalpel (in 16th cent. scalpelle), Germanskalpel.

a. A small light knife used in surgical and anatomical operations.

49 "There anatomic art would scan

50 The wonders of the inner man

51 And range them on the shelf;

52 While, as the keen scalpel dissects,

53 Keen speculation oft detects

54 The very soul itself."

- Ode To Glasgow College (1838)

Fig. 1 Various surgical tools on display in The Wellcome Collection's Exhibition: Medicine Man. E26, E25, E24 are all examples of Scalpels used during the 18th and 19th Century

At first glance, it may seem unlikely that the surgical scalpel has much of a story to tell. Its practical use has been unchanged for centuries. Indeed, the scalpel appears in the above image (Fig. 1) much as it would in a surgeons inventory today. A short, sharp blade, and a handle of ergonomic length to be held one hand; it's design and purpose is very simple. During the course of the 18th Century, however, the scalpel experiences a profound literary moment. The years between 1700 and 1799 are hugely significant in the history of surgery, because the advances in knowledge of the human anatomy provided budding surgeons with the opportunity to perform extensive surgeries with increasing frequency. 18th century surgeons carried out their craft before the invention of anesthesia, which only came about in the early years of the 19th century. October 16th, 1846 marks the first successful surgery performed where the patient was subdued by anesthesia. It can be imagined then, that the scene of surgery throughout the years in question is a terrain of excruciating trial and error. Surgery was an invasive way to learn anatomy. Indeed, in a society developing a much keener and scrutinising interest in and understanding of human anatomy, and experiencing advancements in technology and science that enable a yearning for a deeper knowledge of the internal workings of the body, the scalpel emerges as a tool of curiosity and medical empowerment. The status of the 18th Century's understanding of the human body, disease and decay can only be described as developing; the scalpel is the tool which allowed this curiosity to thrive.

A Moment in Time:

Google Ngram indicating the frequency of the term "Scalpel" in the English Language (1700-1800)

The above Google Ngram demonstrates, visually, the exponential significance of the scalpel during the 18th Century. While this is merely an indication of the prevalence in the language of the word itself, it provides a valuable insight into the breadth of significance this particular tool gained during the course of 100 years. It becomes obvious that through the rapid advancement of medicine and the surgical profession that characterises these years, the scalpel became, in the latter years of the century, a well-versed tool. The scalpel will have been increasingly used with more precision and confidence, thus, as an initial curiosity pertaining to "insides" is satiated, the scalpel obtains a more nuanced surgical purpose. Beginning as a tool serving an intellectual intrusiveness, by the end of the century, the scalpel has undergone a transformation in its seemingly singular identity of incision making. There is a significant peak in frequency beginning circa 1780, marking a moment in which the scalpel breaks its practical bounds in surgery and medicine. Having gained, intellectually, what it can from its objective utility, the century begins to respond to its subjective purpose. The fact that the scalpel begins to appear in English fiction following 1780 is a symptom of this transformation. Through scrutiny of the scalpel's journey through the century, what comes to light is a society coming to terms with breaking the humanity's skin, first literally and then figuratively; this is what I hope to demonstrate in the following exploration.

Google Ngram indicating the frequency of the term "Scalpel" in English Fiction (1700-1800)

Exploration & Macabre Curiosity:

Surgery in the 18th Century

Fig. 2 Interior with a surgeon attending to a wound in a man's side by Johan Joseph Horemans (1689 - 1759)

Fig. 2 Interior with a surgeon attending to a wound in a man's side by Johan Joseph Horemans (1689 - 1759)

Oil on Canvas, Flemish, c. 1722

Medicine Man, The Wellcome Collection, London

As is indicated by Fig.2, the role of the surgeon in the 18th century can be seen as almost domestic. Surgery would often take place in the patient's home: the surgeon would bring with him his tools, and perform the procedure in the patient's bedchamber, or wherever was most convenient. Hospitals were widely associated with poverty and infection, so, despite many Hospitals originating during the 18th Century - specifically in London - it was generally preferred, by those who could afford it, to have surgical procedures performed at home. In the above image the surgeon descends on a patient while he is still dressed, in what seems to be the kitchen of the house. What is indicated here, is the immediacy with which surgeon's would have been required to work. Surgical intervention was often an emergency measure, and the use of the scalpel to penetrate the patient's skin can be seen to be relatively imprecise. As well as this, the painting underpins the idea that, while it was widely known that the cleanliness of an open wound was paramount to the patient's survival, this did not extend as far as to sterilise equipment or surroundings. We will see in the Journal's that follow, making an incision using the scalpel was often the first step in an invasive procedure, the only purpose of which was to attempt to find cause for ailment or symptom. Advancements in understanding anatomy came often from surgeon's mere curiosity as to the patient's internal condition.

Medical Journals

Fig 3. Title Page: Miscellaneous Observations in the Practise of Physick, Anatomy and Surgery.With New and Curious Remarks in Botany. Adorn'd with Copper Plates. (1718)

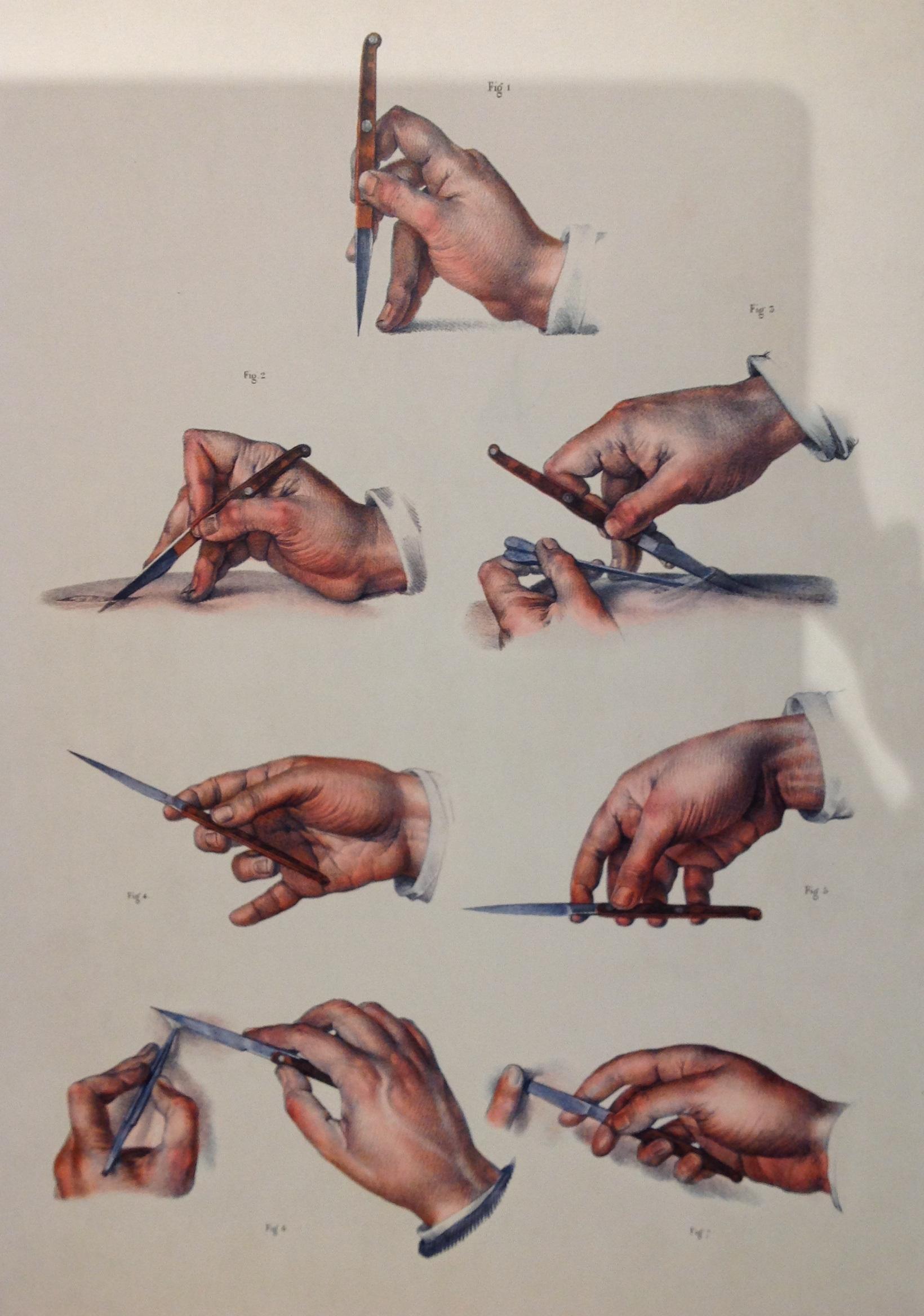

There are countless medical journals that circulated during the 18th Century that paint an informative, if sometimes unsettling picture of the surgical profession of the time. Often the surgical accounts are formulated in letters from one physician to another, as is demonstrated by the excerpt below (Fig. 3). In this publication, Dr. Patrick Blair recounts his various "observations" in brief chapter descriptions of particular procedures, which seems to have been common practice for most physicians at the time. The sharing of surgical discoveries that circulated in the medical profession served to create both a catalogue of anatomical knowledge, but also served to instruct. Blair, for instance, often makes remarks pertaining to the proper use of tools (demonstrated also by the illustrations in Fig. 5) and the appropriate remedies for particular symptoms and side effects that arise from the patient's distress during the procedure. Post-mortem surgeries make up a large portion of these kinds of journals, as often the patient described dies of an unidentified disease, after which the surgeon performs a kind of autopsy, but with the origins of the disease that caused the death of the patient being yet unidentifiable, this was often a series of incisions motivated by sheer curiosity.

Fig. 4 Contents pages: The Philosophical Transactions from the Year M DCC. In Two Volumes., detailing section: The Anatomical and Medical Papers (pp. 22-24)

Fig. 5 Sketches detailing the correct use of a Scalpel by anonymous artist

Date unknown

Medicine Man, The Wellcome Collection, London

The Body:

Exploratory Surgery & Dissection

Fig. 6 William Cheseldon giving an anatomical demonstration at the anatomy theater of the Barber-Surgeons' Company

Oil on canvas, British, c. 1730/1740

Medicine Man, The Wellcome Collection, London

As is demonstrated aptly by the contents pages to The Philosophical Transactions above (Fig. 4) the progression of 18th century surgery really took place organ by organ. The scalpel in this instance truly represents the exploratory nature of this particular society's yearning for biological knowledge. This is indicated by the popularisation of the surgical theater, which became a central stage for intellectual advancement in the surgical field, often admitting up to 450 onlookers while procedures were performed on live patients. In the above image (Fig. 6), a figure that we understand to be William Cheseldon is moving towards the patient's torso with a scalpel, about to make an incision between his ribs. The scene exudes a sense of intellectual engagement; the book in the foreground - presumable a medical journal depicting the correct procedural conduct, and the implicit stillness of the patient, seems to imply that this particular incision will have an exploratory purpose. The scalpel will be used to open up the body for the onlookers scrutiny.Presumable the figures surrounding Cheseldon are practicing surgeons, hoping to be informed and instructed by the procedure they are about to witness. In terms of the significance of the scalpel, then, we can infer that in this earlier context of surgery the scalpel is a relatively unrefined tool. Its primary use is simply to break the surface of the skin, and to systematically penetrate orifices of the body in order to display another layer of human biological function.

This procedure is taking place in the theater of the Barber-Surgeon's company, which brings us to another interesting advancement in the medical society of the time. In the history of western, specifically English medicine, barbers and surgeons were tied together in their function within the medical profession. There are records dating back to the 1300s that depict Barbers as the primary aid for monks, the traditional medical practitioners of the time. The article titled "Worshipful Company of Barbers" by Wikipedia asserts that, "after the licensing of dissection in 1540, public demonstrations took place four times a year in the Great Hall of Barber-Surgeons' Hall - with a crowd surrounding a table. Attendance was compulsory for all 'free' surgeons." The idea, as is demonstrated by Fig. 6, that surgeons held a responsibility to educate themselves about the inner workings of the body, in order to extend their skills in diagnostics and healing, was already concrete. However the 18th Century saw the secession of Surgeons from this partnership with the Barbers. In 1745 the surgeons broke away to form the Company of Surgeons, which would later become the Royal College of Surgeons, in 1800. In essence this secession represented a refinement in the role of surgeons in the medical field, and indicates to us a significant moment in the rise of professionalism of surgical practice. Surgery became a medical profession in its own right.

Many of the medical publications of the time included etchings on copper plates that indicated the structure and function of independent orifices and organs. Below are examples taken from the Heart and Abdomen chapters of The Philosophical Transactions publication depicted above (Fig. 4). Again the utility of the scalpel as a tool for exploration is exemplified. To create etchings such as these, a surgeon would have had to undertake meticulous dissections of every part of the human body. The scalpel was the only way to achieve this. The precision of cuts required to splay organs out in the way indicated below would have required a methodical refinement of the surgeon's skill. Useful discoveries could only be made if the incisions were precise and accurate within the perimeters of a millimeter. The detailed labeling of the diagrams below are indicative of just how intricate the surgeon's work became, once the scalpel had allowed him to penetrate the smallest orifices of the human anatomy.

Fig. 7 Left: The trunk of the Great Artery opened and dispay'd

The Philosophical Transactions from the Year M DCC. In Two Volumes (pp. 549)

Fig. 8 Right: The Body of the true Bladder

The Philosophical Transactions from the Year M DCC. In Two Volumes (pp. 590)

A closer look at some procedures...

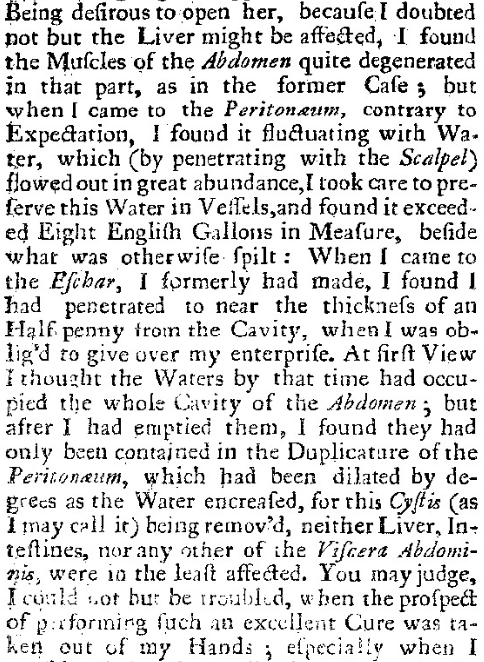

The excerpt shown in Fig. 9 shows the scalpel being used to make an incision in to the dead body of a young woman to extract liquid from the abdomen. It is a post-mortem procedure. The opening line of this paragraph seems to indicate the precise sentiment of exploration that I have alluded to above. Blair writes "being desirous to open her, because I doubted not but the liver might be affected..." However, upon opening his subject, he finds that "contrary to expectation" his assumption is incorrect and her abdomen is filled with water. The scalpel is then crucial in enabling him to drain the liquid from the woman's body, however, since she is already deceased, the soul purpose of his collecting it is to make an educated assumption as to the conditions of her death. The lack of precision in the medical assessment of his subject is indicated in his measurement he gives: "it exceeded eight English gallons in measure, besides what was otherwise spillt". The progression of this procedure makes the purpose of the scalpel quite clear; the surgeon, through an innate and "desirous" curiosity, is driven further and further in to his exploration of the internal condition of his patient's abdomen. The scalpel is the indispensable tool that enables this exploration.

Fig. 9. Selected paragraph from Dr. PatrickBlair's

A Letter from Dr. Patrick Blair to Doctor Baynard.

Containing Some Considerable Improvements

concerning the Use of Cold Bathing. (pp. 36)

This particular excerpt is indicative of a lack of refinement in the use of the scalpel. Blair records the condition of his patient's hand over several pages, and describes, there, the exponential growth of a tumor. The paragraph is permeated with the grotesque realities of surgery in the 18th century. It can be inferred contextually that this procedure would have taken pace in the home of the patient, and at the point at which Blair makes the incision, one is reminded of the nonexistence of anesthesia. The use of the scalpel to perform the removal of the tumor gives us an interesting insight in to the development of the tool itself. Blair writes he "cut it off not without difficulty, for my scalpel had scarce force enough to cut through the bone." Whether an incident of misuse, or lack of judgement on the surgeon's part, it is indicated that his use of the scalpel is opportunistic and inappropriate. Again, the implication is that this is is a previously unknown affliction, and the surgeon relies on the scalpel to facilitate his surgical advance. In its simplistic utility the scalpel enables the surgeon to experiment with its use, and apply its blade to an unidentified affliction. The opportunistic performance of the incision is central to the innovative and progressive nature of surgery in the 18th century.

Fig. 10 Selected paragraph from Dr. PatrickBlair's

Miscellaneous Observations in the Practise of Physick,

Anatomy and Surgery. With New and Curious Remarks

in Botany. Adorn'd with Copper Plates. (pp. 51)

Similar to the above procedure, here a different physician is faced with a surgical limitation. "Cholick", a prevalent condition of the abdomen in the 18th century, has cause the death of this patient, and the surgeon attempts to penetrate the abdomen to discover the precise cause of the disease. Again the lack of refinement in technique and tools is made clear. The scalpel is almost unable to penetrate the patient's petrified abdomen, from which it can be inferred that the resulting incision would not have been delivered with much accuracy. What can be read here, however, is the surgeon's intimate knowledge of the abdomen. We can see here the manifestation of a growing knowledge of anatomy that we know to have taken place during the century. Despite severe swelling and inflamation, the psysician is able to determine the "pancreatick vein" and locate the apparent "haemorhage". As well as this, his recording of the body's biological reaction to death is meticulous. The scalpel, here, allows for a detailed capture of the body's reaction to this particular disease: Cholick.

We can see, then, that this kind of post-mortem dissection was crucial to the surgeons growing understanding of the body's biological functions. The opportunity, facilitated by the scalpel, to scrutinize the state of this patient's abdomen will have contributed greatly to the wider advancement of surgical practice in this area.

Fig. 11 Selected paragraph from The Philosophical

Transactionsfrom the Year M DCC. In Two Volumes. (pp. 80)

Turner’s Diary

Fig. 12 Selected paragraph detailing the dissection of Elizabeth Elless from The Diary of Thomas Turner: 1754-1765.

In this section of The Diary of Thomas Turner the reader experiences this tradition of post-mortem dissection second hand, through the eyes of an 18th century tradesman in his domestic setting. Turner's diary provides an invaluable insight into the daily life of the 18th century, and in this instance it confirms, expands, and somewhat colloquialises the insight we have gained from the medical journals into the practice of surgery. Immediately we are privy to the idea that the surgery was not conducted in private; Turner implies several onlookers. It is also made clear that the purpose of the autopsy is to determine if Elizabeth Elless has died of poison. Again, the incisions made have an exploratory purpose, for which the scalpel is the most necessary tool. Turner relays the procedure as if the surgeon is narrating it to him, writing "they first made a cut from the bottom of the thorax to the pubis". Unless we assume that Turner has a partial medical education, this precision of knowledge indicates that the surgery is conducted in part to the benefit of its audience curious intellect. The fact that Turner is able to tell us that "the membranes were all entirely whole", and "the womb full of the water common on such occasions" further indicates the surgeon's oral account of the procedure. The diagram is significant too in the developing refinement of the scalpel's utility. Contrary to some of the procedures detailed above (Fig. 9, 10, 11), the T shaped incision suggests a much more procedural use of the scalpel. Implicitly, the shape of this particular incision provides the most convenient access to the abdomen, and provides us with an indication of a developing methodical conduct in surgery. We will discover more such specific instructions for the making of incisions in the section concerning midwifery.

Another interesting inference from Turner's Diary is the idea of post-mortem dissections and their relevance to the deliverance of justice. The possibility of performing exploratory autopsies allowed, in the 18th century, for a heightened scrutiny of murder cases. When discussing Satire in a later section, we will become more closely acquainted with this discussion, however, in terms of Elizabeth Elless, it is curious that her implicit murderer, Peter Adams, and any notion of his suffering consequence, is overshadowed by the surgical procedure determining Elizabeth's cause of death. It seems that the procedure itself becomes the murder trial. The surgeon's conclude form their findings that it can not have been poison that killed her, and "if anything else had been administered, it had been carried off by her violent vomiting and purging". This is the extent to which her case is pursued in the narrative. Peter Adams continues to appear in the diary following this incident, and is clearly never indicted with the murder of Elizabeth Elless. To readers this indicates the infancy of this particular system of justice. However, with the opportunities that the advancement of surgery provided, which in this narrative seemingly breaks the bounds of a strictly medical purpose, the scalpel obtains a new significance: a judicial purpose is absorbed into its subjective identity.

The Scalpel and Midwifery:

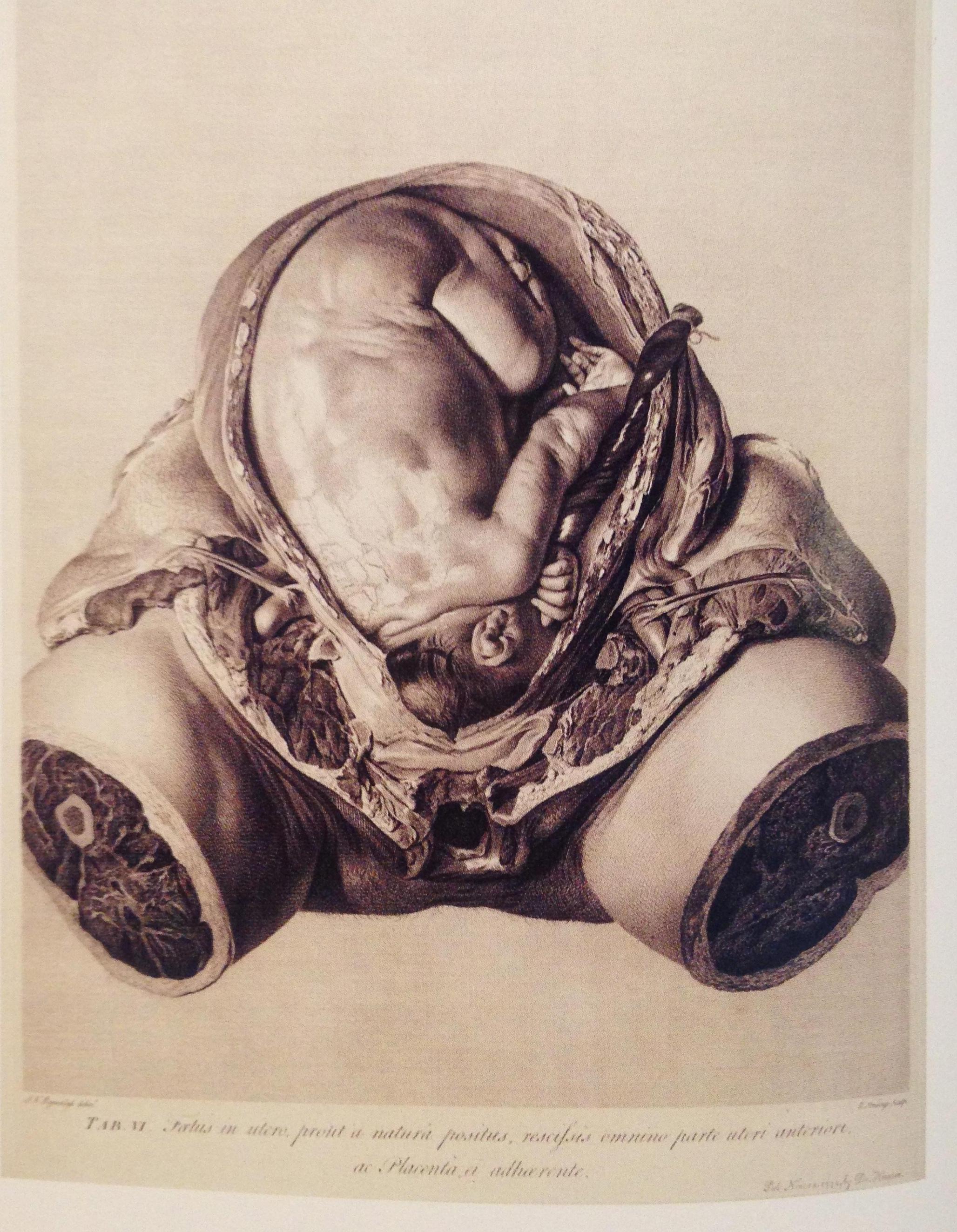

The image below indicates, once again, the utility of the scalpel as a tool of anatomical exploration. From the sketch we can infer the incisions made to produce the image. This imagine, however, is a stark indication of the macabre curiosity inherent in 18th century medicine. The child, encased in the disembodied womb of its mother, is a horrific image to behold despite the medical significance of this hyper-realistis depiction. The detail surrounding the infants body, including the umbilical chord, the various layers of the uterean membrane, and the minute detail with which the matter surrounding the uterus is depicted, contrarily works to completely dehumanise the subject of scrutiny. As inferred by the caption, the drawing was produced to indicate the natural position of a child shortly before its birth. The dismemberment of the human body, here, mirrors the contents pages depicted in the first section (Fig. 4) and also carry an unsettling similarity to the organs etched in to copper plates by the author of The Philosophical Transactions from the Year M DCC.: (where Mr. Lowthorp Ends) to the Year M DCC XX. Abridg'd, and Dispos'd under General Heads. In Two Volumes. The scalpel that enabled the production of all these images becomes a ruthless tool of macabre utility. Specifically when related to the subject of midwifery, the role of the scalpel in the facilitation of new life is an interesting one to deconstruct.

Fig. 13 The Child in the Womb, in its Natural Situation from William Hunter's Anatomia uteri humani gravidi (The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus) (1774)

Medicine Man, The Wellcome Collection, London

Extracting the Child:

The involvement of the scalpel in midwifery indicates the newness of the profession in the 18th century, and the frequency of necessity for emergency measures during the birth of a child. A General Treatise of Midwifery dedicates an entire section to the use of tools, however, in the opening statement declares that "instruments are never to be made use of but when there is an absolute necessity for it". The passage following indicates the varying instances of necessity, and continues to describe which tools would be appropriate in each situation. The scalpel features here as a tool only required when the child is born already deceased: "to make an incision in the child's head for to introduce the tire-tete". The tire-tete being a version of the forceps specifically designed to grip the head of a dead infant. Again we are reminded that the 18th century really encompasses a moment in medical history that is wrought with the most innovative and drastic advancements. The increasingly specific and developing understanding of the anatomy receives a new layer of significance when there are two human bodies involved: that of the mother and of the child. The pursuit of the significance of the scalpel during the 18th century must include the practice of midwifery, as for the birth of a child the surgeon and midwife were required to work in conjunction to preserve the life and health of both the mother and the infant.

Fig. 14 Selected pages from A General Treatise of Midwifery (1719) detailing the tools required to extract a child from its mother (pp. 247-249)

Fig. 15 depicts the varying kinds of Forceps used alongside the scalpel in particularly difficult procedures. What is most interesting about these particular tools, is their variations, contrary to the scalpel, which remains almost entirely unchanged. A more detailed analysis of the forceps here: http://eighteenthcenturylit.pbworks.com/w/page/70318982/Forceps

Fig. 15 Surgical Forceps on display:

Medicine Man, The Wellcome Collection, London

Fig. 16 depicts a typical birth scene during the 18th century. While this particular image does not involve the use of a scalpel, it is significant to note that, as with the practice of surgery, almost all children would have been birthed at their mother's home. Considering this, then, the emergency measures described in Fig. 14 would have required the surgeon and midwife to be prepared with an extensive inventory of his equipment for every birth. In particular, as we will find in the next section, the necessity of a cesarean birth would have provided a particularly difficult test of the surgeon's skill.

Fig. 16 Oil Painting of a Birth Scene

Oil on paper, possibly French, c. 1800

Medicine Man, The Wellcome Collection, London

Cesarean Operation:

A cesarean operation, as indicated in A General Treatise of Midwifery, was only performed on women who have died in labour. The author states “there are few who are as cruel and barbarous as to undertake to make the caesarean incision on a woman alive” (274). Here we are reintroduced to the methodical incision that is depicted by means of a diagram in the Diary of Thomas Turner:

Scalpel (A): used to make a half moon incision around the womb if the mother is alive.

If the mother has died, the scalpel is used to make a longitudinal incision. (253)

Fig. 17 Instruments for the Cesarean Operation, including the Scalpel

taken from A General Treatise of Midwifery (1719) (pp. 253)

While the cesarean operation can be dated back as far as the Greeks, its practice in the 18th century was vastly affected by the aforementioned medical advancements that characterised this century. The scalpel, indicated in yellow in the above image, is the most vital tool to perform this procedure. An intimate knowledge, therefore, of the anatomical structure of the womb, was paramount to ensure the safety of the child. Another look at Fig. 13, re-examined from the perspective of a surgeon required to perform a cesarean, indicates just how difficult the first incision would have been to make. A General Treatise of Midwifery provides the reader with a very specific instruction on how to proceed with the scalpel (Fig. 18). Here, again, the relatively unrefined nature of the tool's utility is exemplified. The author gives an indication of the depth of the required incision, and relates the various orifices through which the surgeon must cut before he enters the womb. What is alarming here is the impreciseness of the instruction. The notion that a surgeon may go "very inconsiderately and rudely to work" (255) with a scalpel, paints a grotesque picture of the surgical procedures that are implicitly taking place during time this treatise was published. It provides a brief, yet profound insight into the varying degrees of professionalism one would have been able to find within the surgical profession. The scalpel, here, represents a tool entirely at the mercy of the advancement of the surgeon's skill.

Fig. 18 Selected paragraph taken from A General Treatise of Midwifery (1719) (pp. 255)

Emergency Measures:

Descriptions, recorded by surgeons of the 18th century, of the surgical procedures required to execute difficult births, are inherently opportunistic in their tone. The implication, as with the procedures previously described in the medical journals of Dr. Patrick Blair, which would have each contributed to the particular knowledge of a specific part of the human anatomy, is that the practice of each birth served to inform the yet developing knowledge of labour and birth itself. Fig. 19 describes the implementation of the scalpel in an emergency measure that saved the life of both the mother and the child (210). Here the surgeon intervenes when the mother is seen to be "just expiring" (210), and the midwives deliver her "into (his) hands to do with her what (he) thought fit" (210). The scalpel, again, is the surgeon's opportunistic tool. The surgeon reveals the interior of the womb, using the scalpel, and is thus able to proceed with the correct procedure to extract the child. However, the eventual consequence of such a hasty remedial action is also detailed in this paragraph: "ever since she was delivered she hath suffered a prolapsis uteri upon the least standing or walking" (210). Here we are reminded that surgical precision, in the 18th century, is in its infancy. This particular description of a mother's lasting condition following such a difficult procedure exemplifies the vast potential of consequences caused by poorly conducted surgery.

Fig. 19 Selected paragraph taken from The Philosophical Transactions Abridged and Disposed under General Heads (1733)

Fig. 20 A grotesque accouchement

Fig. 20 A grotesque accouchement

Oil on canvas, Italian, 17th Century

Medicine Man, The Wellcome Collection, London

Wounds and Wine:

Fig. 21 Selected paragraph taken from A General Treatise of Midwifery (1719) detailing the use of wine to bathe a newborn (pp. 254/5)

A surprising discovery in the exploration of midwifery revealed the use of liquors and "warm wine" to soothe wounds, to serve as a disinfectant, and to recover a child "out of its weakness" (254) following a traumatic birth. 18th century society was aware of the medicinal virtues of alcohol, and wine in particular seemed to be administered for most ailments. The invasive nature of surgery, however, called upon the use of it for cleansing purposes in particular. 18th century society was afforded with the knowledge that water was often unclean and infected--and often the cause of conditions such as cholic. Wine, therefore, could play a significant role in midwifery and surgical procedures. The significance and utility of wine in the 18th century is more widely explored here: http://eighteenthcenturylit.pbworks.com/w/page/101683687/Wine

The Literary Dawn of the Scalpel:

The Travelling Surgeon's Tool

Fig. 22 A surgical Etui with instruments by Savigny (c. 1750).

Top: folding thumb lancet and scalpel.

From left: tongue blade, ear scoop, probes, shagreen case, tweezers, and scissors

One of the main reasons for a surgeon to travel during the 18th Century was the gradual expansion of the British Empire. The above etui shows the collection of tools a surgeon would have travelled with under the service of the navy; the scalpel, of course, being one of the paramount tools within this very select set. The Adventures of Roderick Random by Tobias Smollett is a fictional account based on the author's experiences as a naval surgeon's mate. The protagonist, in a series of adventures, travels the globe, including the West Indies and South America, making his way within the communities by means of his skills as a surgeon.

"But it was not in the power of rum to elevate the purser, who sat on the floor wringing his hands, and cursing the hour in which he left his peaceable profession of a brewer in Rochester, to engage in such a life of terror and disquiet. ---While we diverted ourselves at the expence of this poor devil, a shot happened to take us between wind and water, and its course being through the purser's store-room, made a terrible havock and noise among the jars and bottles in its way, and disconcerted Mackshane so much, that he dropt his scalpel, and falling down on his knees, pronounced his Pater-noster aloud; the purser fell backward and lay without sense or motion; and the chaplain grew, so outrageous, that Rattlin with one hand, could not keep him under; so that we were obliged to confine him in the surgeon's cabbin, where he was no doubt guilty of a thousand extravagancies. ---Much about this time, my old antagonist Crampley came down, with express orders (as he said) to bring me up to the quarter-deck, to dress a slight wound the captain had received by a splinter. His reason for honouring me in particular with this piece of service, being that in case I should be killed or disabled by the way, my death or mutilation would be of less consequence to the ship's company, than that of the doctor or his first mate. ---At another time, perhaps, I might have disputed this order, to which I was not bound to pay the least regard; but as I thought my reputation depended upon my compliance, I was resolved to convince my rival that I was no more afraid than he, to expose myself to danger. ---With this view, I provided myself with dressings, and followed him immediately to the quarter-deck, through a most infernal scene of slaughter, fire, smoak, and uproar! Captain Oakhum, who leaned against the mizen mast, no sooner saw me approach in my shirt, with the sleeves tucked up to my arm-pits, and my hands dyed with blood, than he signified his displeasure by a frown, and asked why the doctor himself did not come?" (Smollett 287/8)

In the above passage it is made clear how essential the doctor, surgeon, and the surgeon’s mate would have been to the company of a naval ship, as well as indicating the dangers of travelling on a vessel committed to the pursuit of Empire. Roderick, when called upon to dress the captain’s wound, recognises that his “reputation depended on (his) compliance” (287), and thus, despite the inference that his skills are not being as practiced as the ship’s primary doctor, he proceeds with his equipment to the captains quarters. Here we are highlighted to an element of the surgical profession that is inextricably tied with the advancement of the British Empire; the surgeon plays a decisive role in this scene, administering a dressing to the ship’s captain, who represents an undeniable symbol of the British conquests. The attack that rock’s the ship and causes the surgeon to drop his scalpel can be read as a metaphorical disarmament here. Roderick, as a subordinate, is forced to intervene because Mackshane, the lead surgeon, is invaluable to the ship’s company. If the surgeon is lost, or rendered incapable, implicitly the entire conquest suffers.

The setting of the naval ship is also significant here. The surgeon, with limited equipment and resources, would have had to be adaptable in his approach to performing procedures, and would have to undertake the same danger as the naval officers while performing his profession. To reach the captain, Roderick is forced to travel “through a most infernal scene of slaughter, fire, smoak, and uproar” (287), and administer a dressing out in the open of the “quarter deck” (287). We are reminded again of the open setting of the surgical theatre, the kitchen scene in Fig. 2, and the notion that a surgeon’s work during the 18th century was distinctly required to be mobile. The ship, however, adds another element of risk to this already unsanitary environment; imagine the use of a scalpel to make a crucial incision while on the deck of a ship under attack.

In another account of the travelling surgeon in the empire, “A specimen of the black art”, we are given a picture of the scalpel that reveals the racism and prejudice that accompanied the British pursuit of Empire in the 18th Century. The short story depicts the return of a lieutenant to his wife, who gives birth to a child born of miscegenation. The surgeon uses the scalpel to penetrate in to the childs body, whose skin shows “not a single white spot” (271) whose head is beginning to show the “frizzled hair” (271) indicative of the local people of the West Indies. The surgeon goes to work to discover the origins of the child’s colouring, and upon slicing open his flesh to reveal the bone the narrative reveals the inherent racial paranoia of the 18th Century’s imperialist ideals: “The experiment was now complete; he opened the wound, and starting back apparently struck with horror, threw down his knife, and swore the child was in fact an imp of the devil, for he could see black to the bone, and the bone black also” (272). Here the scalpels exploratory utility, and its use in the ongoing advancement of ananatomical knowledge, becomes inextricably associated with imperial paranoia and is indicative of an 18th century notion that the anatomy of anyone “other” to the western human carries an entirely different medical significance.

The Scalpel of Satire

Here the scalpel plays its part in the 18th century’s satirical response to the Murder Act of 1751, which allowed the body’s of murderers to be submitted to surgeons in order for them to conduct experimental and educational dissections. The idea was grounded in the notion that a dissected body would continue to suffer after death, and thus this was a way to extend the murder’s sentence beyond hanging, and in to his afterlife. Satire during the 18th century was greatly centred in politics, with figures such as Swift, Pope, and Hogarth all responding to the turbulent politics of the time in their own satirical styles. The images below depict a political conflict coagulated in a satire of the contemporary discourse surrounding dissection. The scalpel performs its well-versed invasive utility to examine in depth the shortcomings of the “late secretary of state” in an extended satire. In Fig. 25, the artist has reversed this satire, and shows William Pitt leading the dissection of the Prince of Wales. The exploration of False Teeth to be found here: http://eighteenthcenturylit.pbworks.com/w/page/102317956/False%20Teeth expands on the significance of satirical art in the 18th century, including more work by artist Thomas Rowlandson.

Fig. 24 (Left) Title Page: Pitt's Ghost. Being an account of the Death,

Dissection, Funeral Procession, Epitaph, and Horrible Apparition,

of the much lamented Late Minister of State.

Fig. 23 (Right)Title Page: Admirable Satire on the Death, Dissection,

Funeral Procession, and Epitaph of Mr. Pitt (1795)

Fig. 25 William Pitt the younger and his ministers as anatomists dissecting the body of the Prince of Wales by Thomas Rowlandson (1788/89)

Wellcome Library no. 12174i, Wellcome Collection, London

The Metaphorical Scalpel:

Erasmus Darwin was an English physician, and one of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave-trade abolitionist, inventor and poet. Below James Montgomery offers a critical response to his poem "The Botanic Garden" which indicated the beginnings of the scalpel's transition into metaphor. Montgomery describs Darwin by saying "he appears a petit-maître of the scalpel" (Montgomery 147), attributing to his poetic style the kind of invasive and exploratory nature we have come to associate with the scalpel throughout the remainder of the century.

Dr. Darwin has splendidly exemplified the effects of his own theory, which certainly includes much truth, but not the whole truth. Endued with a fancy peculiarly formed for picture-poetry, he has limited verse almost within the compass of designing [Page 145 ] and modelling with visible colours and palpable substances. Even in this poetic painting, he seldom goes beyond the brilliant minuteness of the Dutch school of artists, while his groups are the extreme reverse of theirs, being rigidly classical. His productions are undistinguished by either sentiment or pathos. He presents nothing but pageants to the eye, and leaves next to nothing to the imagination; every point and object being made out in noonday clearness, where the sun is nearly vertical, and the shadow most contracted. He never touches the heart, nor awakens social, tender, or playful emotions. His whole "Botanic Garden" might be sculptured in friezes, painted in enamel, or manufactured in Wedgwood ware. "The Loves of the Plants" consist of a series of metamorphoses, all of the same kind,---plants personified, having the passions of animals, or rather such passions as animals might be supposed to have, if, instead of warm blood, cool vegetable juices circulated through their veins; so that, though every lady-flower has from one to twenty beaux, all flighted and favoured in turn, the wooings and the weddings are so scrupulously Linnæan, that no human affection is ever concerned in the matter. What velvet painting can be more exquisite than the following lines, in which the various insects are touched to the very life?---

"Stay thy soft murmuring waters, gentle rill;

Hush, whispering winds; ye rustling leaves, be still;

Rest, silver butterflies, your quivering wings;

Alight, ye beetles, from your airy rings; [Page 146 ]

Ye painted moths, your gold-eyed plumage furl,

Bow your wide horns, your spiral trunks uncurl;

Glitter, ye glow-worms, on your mossy beds;

Descend, ye spiders, on your lengthen'd threads;

Slide here, ye horned snails, with varnish'd shells;

Ye bee-nymphs, listen in your waxen cells."

In such descriptions Darwin excels, and his theory is triumphant; but to prove it of universal application, it must be put to a higher test. In the third canto of the "Botanic Garden," Part II., there is a fine scene---a lady, from the "wood-crowned height" of Minden, overlooking the battle in which her husband is engaged. As the conflict thickens, she watches his banner shifting from hill to hill, and when the enemy is at length beaten from every post,

"Near and more near the intrepid beauty press'd,

Saw through the driving smoke his dancing crest;

Saw on his helm, her virgin hands inwove,

Bright stars of gold, and mystic knots of love;

Heard the exulting shout, 'They run, they run!'

'Great God!' she cried, 'he 's safe, the battle's won!'

---A ball now hisses through the airy tides,

(Some fury wing'd it, and some demon guides,)

Parts her fine locks her graceful head that deck,

Wounds her fair ear, and sinks into her neck;

The red stream issuing from her azure veins,

Dyes her white veil, her ivory bosom stains!"

[The Botanic Garden Part II: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/10671 ]

Every syllable here is addressed to the eye; there is not a word for the heart; the poet himself might have been the bullet that shot the lady, so insensible is he of the horror of the deed. Or he might have been a surgeon, deposing before a coroner's inquest [Page 147 ] over the body, under what circumstances said lady came to her death, so anatomically correct is the process of the wound laid down; yet, even in that case, he appears a petit-maître of the scalpel, so delicately does he talk about---mark well the epithets!---the " fine locks," the " graceful head," the " fair ear," the "neck," the "red stream," the " azure veins," the " white veil," and the " ivory bosom;"---a perfect inventory of the lady's charms; without a sigh, a tear, or the wink of an eyelid, over the matron slain between her two children, the wife struck dead in the presence of her husband returning victorious from battle to her embrace. This may be poetry, but it is not nature; and such, in every instance, more or less, is the poetry which is formed according to artificial rules.

The Surgeon's Song

Fig. 26 The Surgeons Song (1838)

The Scalpel and The Self: Narrative and Internalisation

Under the Knife, H.G.Wells

There must have been an interval of absolute unconsciousness, seconds or

minutes. Then with a chilly, unemotional clearness, I perceived that I was

not yet dead. I was still in my body; but all the multitudinous sensations

that come sweeping from it to make up the background of consciousness had

gone, leaving me free of it all. No, not free of it all; for as yet

something still held me to the poor stark flesh upon the bed--held me, yet

not so closely that I did not feel myself external to it, independent of

it, straining away from it. I do not think I saw, I do not think I heard;

but I perceived all that was going on, and it was as if I both heard and

saw. Haddon was bending over me, Mowbray behind me; the scalpel--it was a

large scalpel--was cutting my flesh at the side under the flying ribs. It

was interesting to see myself cut like cheese, without a pang, without

even a qualm. The interest was much of a quality with that one might feel

in a game of chess between strangers. Haddon's face was firm and his hand

steady; but I was surprised to perceive (_how_ I know not) that he

was feeling the gravest doubt as to his own wisdom in the conduct of the

operation . . .

***

. . . Then, suddenly, like an escape of water from under a lock-gate, a great

uprush of horrible realisation set all his thoughts swirling, and

simultaneously I perceived that the vein was cut. He started back with a

hoarse exclamation, and I saw the brown-purple blood gather in a swift

bead, and run trickling. He was horrified. He pitched the red-stained

scalpel on to the octagonal table; and instantly both doctors flung

themselves upon me, making hasty and ill-conceived efforts to remedy the

disaster. "Ice!" said Mowbray, gasping. But I knew that I was killed,

though my body still clung to me.

H. G Well’s short story emerges during the 19th century, and presents the culmination of the scalpel’s transformed subjective identity. The narrative voice in this extract is the surgical patient himself, and the perspective is from within a dying patient. The procedure eventually brings about his death. As we encountered briefly in terms of the macabre curiosity inherent to the 18th century’s approach to medicine, again we are presented with a complete alienation of body and mind. The narrator tells us: “I knew I was killed, though my body still clung to me” (Wells Web.). The invasive connotation of the scalpel, and the exploratory sentiment attached to the scalpel as we encountered it in the medical journals of the beginning of the century, has been absorbed in to the literary tradition of metaphor and internalisation. The scalpel in this subjective state becomes significant to the internalisation of feeling and the depiction in literature of the “self”. The patient describes the experience of the scalpel penetrating his skin and self reflects: “it was interesting to see myself cut like cheese, without a pang, without even a qualm” (Wells Web.). The human body, the anatomy we have encountered previously in the scalpel’s journey through the century, is separated from the human psyche, and the scalpel’s ruthless and graphic utility works to reveal this disconnect. This extract gives voice to the patients that are implied in the documented procedures of Dr. Patrick Blair and other surgeons of his kind. The scalpel’s penetration is at its deepest. It has carved its way through the surface of the skin, through every organ and system of the body, through every remaining membrane and orifice, and has eventually reached the core of the self. By this moment in the early 19th century, the graphic and gruesome history of surgery originating in 1700 has been enveloped by the literary tradition. The 19th century scalpel’s subjective identity is one of invasive penetration, encumbered with the weight of history; that of a developing practice of surgery that, from it’s infancy, forged its way through the 18th century leaving a graphic tale of human pursuit of knowledge at the peril of the body and eventually the mind. What is perhaps most telling of the scalpel’s journey in this text is the narrator’s omniscient knowledge of the surgeon’s own mind. “He is surprised to perceive … that (the surgeon) was feeling the gravest doubt as to his own wisdom in the conduct of the operation” (Wells Web.). The uncertainty with which the narrative colours the surgeon is implicit in the undercurrent of all that we have discovered here. Each procedure, each childbirth detailed in this collection, shows the 18th century surgeon at the experimental edge of innovation in his profession, and reveals, thus, the vast advancement in medicine and surgery that characterised this age.

Bibliography:

Primary Sources:

A Speciment of the Black Art. 1833. Monthly magazine, or, British regster, Feb.1800-June 1836, 16(93), pp. 270-272.

http://search.proquest.com/docview/4534597/6845C9A9686A44E0PQ/1?accountid=14888

Blair, Patrick, Dr. "A Letter from Dr. Patrick Blair to Doctor Baynard. Containing Some Considerable Improvements concerning the Use of Cold Bathing." (1717): n. pag. Historical Texts Jisc. Web.

<https://data.historicaltexts.jisc.ac.uk/view?pubId=ecco-1176001900&terms=scalpel&date=1717-1801&undated=exclude&sort=date%2Basc&tab=date&pageTerms=scalpel&pageId=ecco-1176001900-10>.

Blair, Patrick, Dr. "Miscellaneous Observations in the Practise of Physick, Anatomy and Surgery. With New and Curious Remarks in Botany. Adorn'd with Copper Plates." (1718): n. pag. Historical Texts Jisc. Web. <https://data.historicaltexts.jisc.ac.uk/view?pubId=ecco-0171200700&terms=scalpel&date=1717-1801&undated=exclude&sort=date%2Basc&tab=date&pageTerms=scalpel&pageId=ecco-0171200700-40&illustrated=true>.

Dionis. A General Treatise of Midwifery Faithfully Translated from the French of Monsieur Dionis .. London: Printed for A. Bell, J. Darby, A. Bettesworth, J. Pemberton, C. Rivington, J. Hooke, R. Cruttenden, T. Cox, F. Clay, J. Battley, and E. Symon, 1719. Print.

https://data.historicaltexts.jisc.ac.uk/view?pubId=ecco-0010000100&terms=scalpel&date=1717-1801&undated=exclude&sort=date%2Basc&tab=date&pageTerms=scalpel&pageId=ecco-0010000100-20&illustrated=true

Lang, John Dunmore. "Ode to Glasgow College". Poems: Sacred and Secular: Written Chiefly at Sea, within the Last Half-century. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low, & Searle, 1873. Print.

http://0-literature.proquest.com.pugwash.lib.warwick.ac.uk/searchFulltext.do?id=Z300673376&childSectionId=Z300673376&divLevel=3&queryId=2913848096057&trailId=1529CF187CD&area=poetry&forward=textsFT&queryType=findWork

Smollett, Tobias G. The Adventures of Roderick Random. London: Printed for J. Osborn, 1748. Web.

http://0-literature.proquest.com.pugwash.lib.warwick.ac.uk/searchFulltext.do?id=Z000046671&childSectionId=Z000046671&divLevel=0&queryId=2913848350053&trailId=1529CF3DDEC&area=prose&forward=textsFT&queryType=findWork

Turner, Thomas. The Diary of Thomas Turner: 1754-1765. Ed. David George. Vaisey. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1984. Print.

Wells, H. G. (Herbert George) "Under the Knife." Thirty Strange Stories. Freeport, NY: for Libraries, 1969. N. pag. Print.

The Philosophical Transactions from the Year M DCC.: (where Mr. Lowthorp Ends) to the Year M DCC XX. Abridg'd, and Dispos'd under General Heads. In Two Volumes. Ed. Wilkin, Richard, Ranew Robinson, Samuel Ballard, John Innys, William Innys, and John Osborn. London: Printed for R. Wilkin, R. Robinson, S. Ballard, W. and J. Innys, and J. Osborn, 1721. Print.

https://data.historicaltexts.jisc.ac.uk/view?pubId=ecco-0253100101&terms=scalpel&date=1717-1801&undated=exclude&sort=date%2Basc&tab=date&pageTerms=scalpel&pageId=ecco-0253100101-5900&illustrated=true

The Philosophical Transactions (from the Year 1720, to the Year 1732) Abridged and Disposed under General Heads. By Mr. Reid and John Gray .. London: Printed for William Innys and Richard Manby, 1733. Web.

https://data.historicaltexts.jisc.ac.uk/view?pubId=ecco-0303400102&terms=scalpel&date=1717-1802&undated=exclude&filter=subject%7C%7CReligion%20and%20Philosophy&pageTerms=scalpel&pageId=ecco-0303400102-10&illustrated=true

The Surgeons Song. 1838. Fraser's magazine for town and country, 1830-1869,17(102), pp. 765. Web.

http://search.proquest.com/docview/2650542/3A7EFD27C21E412DPQ/2?accountid=14888

Evans, 32354 Gaines, P. W. Cobbett, 154b A political lampoon on William Cobbett. The confession and dying speech of Peter Porcupine. A re-issue of the May 22 edition. 1797. pp. 25-32. Web.

https://data.historicaltexts.jisc.ac.uk/view?pubId=ecco-1251300700&terms=Dissection&date=1717-1801&undated=exclude&pageTerms=Dissection&pageId=ecco-1251300700-10

Admirable satire on the death, dissection, funeral procession, & epitaph, of Mr. Pitt. Copied from the Telegraph of the 20th, 21st, and 24th of August, 1795. Web.

https://data.historicaltexts.jisc.ac.uk/view?pubId=ecco-0555501900&terms=admirable%20satire%20on%20the%20death%20dissection&date=1717-1801&undated=exclude&pageTerms=Dissection&pageId=ecco-0555501900-10

Pitt's Ghost. Being an account of the Death, Dissection, Funeral Procession, Epitaph, and Horrible Apparition, of the much lamented Late Minister of State. An enlarged edition of the work first published as 'Admirable satire on the death, .. of Mr. Pitt'. London. 1795. Web.

https://data.historicaltexts.jisc.ac.uk/view?pubId=ecco-0052402900&terms=Pitt%27s%20Ghost&date=1717-1801&undated=exclude&pageTerms=Dissection&pageId=ecco-0052402900-10

Secondary Sources:

Montgomery, James. Lectures on Poetry and General Literature, Delivered at the Royal Institution in 1830 and 1831. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Browne, Green, & Longman, 1833. Web.

http://0-literature.proquest.com.pugwash.lib.warwick.ac.uk/searchFulltext.do?id=Z000728015&childSectionId=Z000728015&divLevel=0&queryId=2913848350053&trailId=1529CF3DDEC&area=prose&forward=textsFT&queryTy

pe=findWork

"Worshipful Company of Barbers." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 17 Mar. 2016. <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Worshipful_Company_of_Barbers>.

Images:

Fig. 1, 2, 5, 6, 13, 15, 16, 21: Wellcome, Henry, comp. Medicine Man Exhibit. N.d. This exhibition reunites a cross-section of extraordinary objects from Henry Wellcome's collection. Wellcome Collection, London.

Fig. 22: Greenspan, Robert E. "Cased Surgical Sets." Cased Surgical Sets. Robert E Greenspan, n.d. Web. 16 Feb. 2016. <http://collectmedicalantiques.com/gallery/cased-surgical-sets>.

Fig. 25: Rowlandson, Thomas. William Pitt the Younger and His Ministers as Anatomists Dissecting the Body of the Prince of Wales (Wellcome Library No. 12174i). 1788. Coloured Etching. Wellcome Collection, London.

Fig. 3, 4, 7, 8,9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 26: Selected pages from Primary Sources referenced above

Comments (0)

You don't have permission to comment on this page.