Introduction

In the eighteenth-century, the word 'flute' referred to two different instruments. 'Flute' usually referred to the 'common' flute – otherwise known as a recorder today. On the other hand, what we know as a flute – or the traverse flute – was specifically called the 'German' flute. The latter is what this wiki page will focus on. There are a number of possible reasons given for the name. Firstly, the popularity of the German flute coincided with George I's ascension to the throne. However, even before George I arrived in England, the French referred to it as "flûte d'Allemagne". Therefore, it is likely that the term was introduced by French players who emigrated to London at the beginning of the century.

The flute first featured in an English score in 1701, but the first solo flute performance in a public concert was in 1706 in London. Yet it took until later in the century for the instrument to catch on with the general, middle-class public as a popular instrument to learn. What started as a novelty, became fashionable.

Figure 1: Chart depicting the frequency of the term 'German flute' from 1700-1800 on Historical Texts

Throughout the eighteenth century, the flute underwent many changes. From the mid-seventeenth century, the instrument had been pioneered by the renowned Hotteterre family, and had consisted of three parts: a head joint which is blown into to create a sound; a middle joint with six holes so that the player can produce different notes; and a foot joint with one metal key. Although it had made its orchestral debut in 1681, composing pieces for the instrument did not become fashionable until after 1720. At this time, the middle joint was split into half, so that there were four parts, and added an additional key. Such innovations continued during the eighteenth-century due to German, French, and English flute-makers, but by the end of the period, flutes with 4 or 6 keys were available. Nevertheless, because of how many flute-makers there were and their differing opinions, there was not always uniformity, and different variations were still available.

Costs and manufacture

According to numerous cases detailed in the Old Bailey records, flutes were typically valued around 10 shillings, or around £30 in today's money. This was roughly the same as a violin, despite being an instrument that had only just started to come into vogue. It was therefore an affordable investment for the average middle-class individual with disposable income. They were typically sold in shops owned by the flute-maker themselves. Alternatively, flautists or teachers produced their own flutes, which they then gave out to their students. Because of how technical the process was, and how the smallest changes could greatly affect the sound, it was a profession that required a great amount of expertise on the flute itself. The instruments were often hand-made out of wood: some examples include ebony, fruitwood, or boxwood, but flautist Johann George Tromlitz lists mentions "grenadilla, lignum vitae" (40). Each type of wood had its own timbre and tone. For example, boxwood was said to produce "a pleasing but rather weak tone" but were the "most durable"; ebony, grenadilla, and lignum vitae facilitated a "brighter and stronger" tone, but the former two required a "firm and well-focused embouchure [OED: "The disposition of the lips, tongue and other organs necessary for producing a musical tone"], while the latter had "too little elasticity and [was] more subject to cracking" (40). The joints were then made of ivory, with metal being for keys if there were any. In addition to the material used, because the instrument was still in the process of being developed and perfected, it was possible to buy different variations of the flute at the same time. For example, the number of middle joints varied greatly, from three to around seven. Each version brought its own advantages and issues, as the slightest changes could affect the tuning, for instance. Although rare, there were other types of flute available at the time too that had different ranges, such as piccolos (an octave higher), "the flûte d'amour" (a minor third lower), and "third-flutes" (a minor third higher) (Tromlitz 39).

However, in addition to initial costs, the flute had to be maintained. Typically, the owner was expected to care for their own instrument. Tromlitz gives a detailed account on how he believes the flute should be looked after, in order to keep it in good condition:

…if [the flute] is wiped out dry after playing and laid in a case so that no dust can fall into it; and now and then (once every two, three or four months according to how much it is played and how often it gets wet) given a little oil, it can certainly be kept in good condition for a very long time. […] The best oil is ordinary rapeseed oil…only one should not apply it like those who believe that oil improves the tone, and therefore pour in so much that it runs about inside. Too much oil damages the tone: it deprives the wood of its elasticity… One should use a feather to try to introduce only as much oil as is necessary scarcely to moisten the flute; for oil is necessary not so much for the tone as to help the water run off. (40)

Therefore, in spite of its affordability, it was not a disposable item or one that someone would wish to replace if it could be avoided.

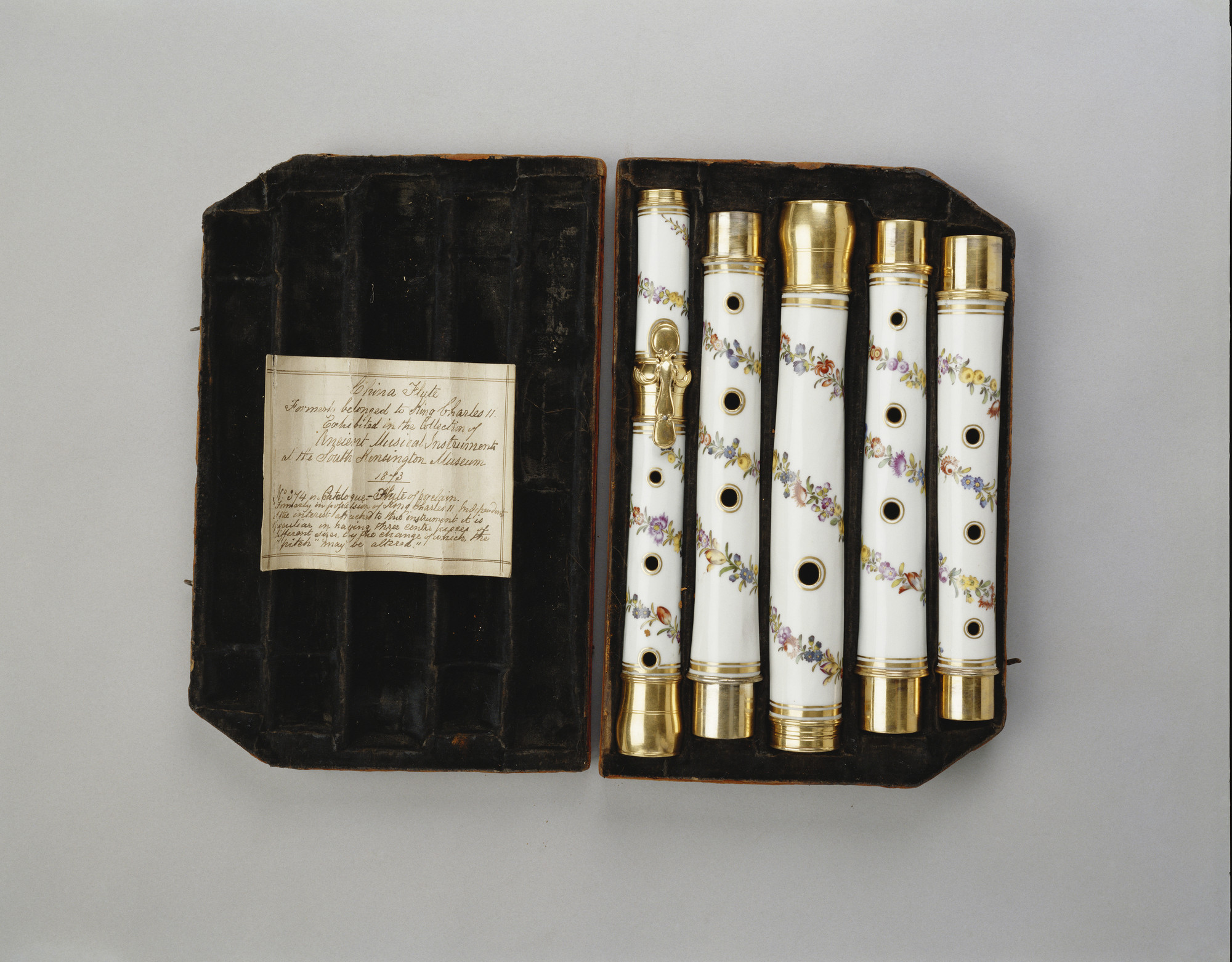

As part of the eighteenth-century porcelain fad, manufacturers experimented with the material and attempted to make instruments out of it, including flutes. This was most certainly not practical: porcelain shrinks whilst being fired in a kiln, so large moulds had to be produced in order to maintain the correct proportions. Once the porcelain had set and had been decorated, a goldsmith would complete the metalwork. For obvious manufacturing reasons, porcelain flutes were quite rare and only the nobility possessed them. Additionally, unlike its cheaper wooden alternative, adjustments could not be made to a porcelain flute's bores; "if a flute is to remain good, it must be rebored after some time" (Tromlitz 26). Despite the fact it was more of a status symbol or object of curiosity, it was still functional and allegedly produced a fine sound.

|

|

|

Figure 2: One keyed porcelain flute in D flat. c.1760-90, South Germany or Saxony, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

|

| Figure 3: Porcelain flute potentially owned by George III, around c.1760, The Royal Collection |

The two flutes pictured above are identical, both likely produced by the same Meissen maker.

Performance and playing

Making a living from just being a musician was by all accounts very difficult. Just as it is today, being a musician was more of a pipe dream than an achievable or practical goal, since it was not really possible to live off the profession's salary; indeed, Tromlitz notes that even those who are employed in a "court orchestra…still get very little" (14). Nevertheless, a great deal of European musicians were attracted to London throughout the eighteenth-century, including some flautists. Jean-Baptiste Loeillet, for example, was a Flemish flautist and composer who settled in London, eventually becoming known as "Jean-Baptiste of London". But the most obvious example is Handel, who also wrote a number of flute concertos and other smaller pieces for the instrument, and came over from Germany to settle in England from 1712 onwards, for most of his career. Even foreign flautists who did not live in England tended to visit London at least once. That is not to say that there weren't any concerts or music outside of London in the period, including flautists, but that the hub of cultural activity was concentrated in the capital.

In the period, performances expanded from simply the private and aristocratic sphere into the public. Flute recitals were typically paired with other instrument's solos. Furthermore, the number of instruments used in ensembles was not fixed; there was no formal orchestral or chamber orchestral arrangement as we have today. Because the flute was not yet a staple instrument, oboists or other woodwind players would play it as a secondary instrument. Benefit concerts were also commonplace, which were put on "in aid of private individuals who had suffered particularly grievous misfortunes" (Mackerness 111). This was entirely organised by the individual whom it was supposed to benefit. Nevertheless, professional musicians were expected to perform in at least one per season.

In terms of notable eighteenth-century amateurs, George III was amongst them, but the monarch who was by far the most well-known for playing the flute was Frederick the Great of Prussia. Not only was he a flautist, but he also composed some 121 sonatas and four concertos for the flute. The music historian and musician Charles Burney (father of Fanny Burney), whilst on a musical tour of Europe, attended one of his concerts at Sans Souci, the king's palace. He describes his performance as surpassing "any thing [he] had ever heard among Dilettanti [gentleman amateurs], or even professors. His majesty played three long and difficult concertos successively, and all with equal perfection" (181). In this particular concert, he "began by a German flute concerto, in which his majesty executed the solo parts with great precision; his embouchure was clear and even, his finger brilliant, and his taste pure and simple (181). In short, he found him to be a very talented flautist indeed.

In addition to playing the flute himself, he also employed Johann Joachim Quantz, a notable and famous flautist in his own right. According to Burney, in 1728 Frederick the Great (who was still a prince at the time) "determined to learn the German flute, and M. Quantz had the honour to teach him" (Burney 192). The monarch was not the only pupil he taught, and he also began to "bore" flutes for them in 1739, "which, afterwards, he found to be very lucrative" (195). He subsequently made numerous changes to the flute, such as adding a second key. He did eventually became a "royal scholar", and was paid rather handsomely: "an annual pension of 2000 dollars for life; a separate payment for compositions; 100 ducats for every flute he should deliver" (195). The King of Prussia was a great patron of music, and this sort of payment is one most musicians could only dream of. Also, Quantz wrote original compositions for the king, but he was "not…permitted to publish them…and have ever since been appropriated solely to [the king's] use" (181). Therefore, not all music was made available to the wider public. Burney is also introduced to Quantz, and is impressed by his technique and ability to execute "rapid movements with great precision" at his age (182); he would have been around 73 at the time, just three years before his death. Though he admits that Quantz's older pieces have "stood their ground very well" (183), he does seem to favour the idea of "innovation" in music, and is somewhat disappointed by the "simplicity" of his pieces:

His music is simple and natural; his taste is that of forty years ago [around the 1730s]; but though this may have been an excellent period for composition, yet I cannot entirely subscribe to the opinion of those who think musicians have discovered no refinements worth adopting, since that time… (182)

The fashion and tastes in music throughout the eighteenth century were so rapidly changing that even a renowned flautist's pieces could become passé within a few decades.

On the other end of the spectrum, writer, poet, playwright, and compulsive gambler Oliver Goldsmith was a flautist himself. Because he was constantly in debt and often had a severe lack of funds, he would use his flute-playing skills to afford "him the means of subsistence, which all his other qualities would have failed to acquire for him" ("Life of Goldsmith" vi). His playing was therefore a way of impressing or pleasing people enough, particularly those of low rank, for them to "welcome" him (vi). As well as entertaining "the peasants of Flanders and Germany" with his flute-playing, he also "produced…a hospitable reception at most of the religious houses that he visited", though his knowledge of the flute was certainly "not profound" (vi). In fact, his basic skills meant that he only pleased the poorer populations; as he confesses, "I must own, whenever I attempted to entertain persons of a higher rank, they always thought my performance odious, and never made me any return for my endeavours to please them" (vii). This is most likely because they would have been more familiar, and more concerned, with proper technique and how it should sound. Nevertheless, his reputation for playing the flute persisted into the following century, as it was depicted in an 1851 painting that was turned into an illustration for his poem, The Traveller.

There did exist music teachers in the eighteenth-century, of varying quality and prices (Mortimer). This included specialists in the 'German' flute. However, these were generally reserved for the more affluent hopefuls who wished to learn the flute. However, there were also an abundance of manuals and instructive books. The first major one to be written was Principes de la flûte traversière, ou flûte d'Allemagne (1707) by Jacques Hotteterre-le-Romain (coming from the same Hotteterre family that had made improvements to the flute), which was translated into English 12 years later. Another notable example is Quantz's 1752, booklet Art of Playing the German Flute, which was incredibly influential. However, there were disagreements between experts on technique, which can be clearly seen in Tromlitz's own 1791 manual, The Virtuoso Flute Player. These would instruct the player on both basic techniques, such as fingering and posture, as well as more complicated issues like expression. Whether or not these instructive books were suitable substitute for teachers was a point of debate. Quantz denies that his book is sufficient for private study without a teacher (Tromlitz 4), but Tromlitz believes otherwise. Furthermore, in his own manual he maintains that his book is for absolute beginners – "even if he has just played his first note" (9) – and wishes to "spare pupils time and money" (4). Though he gives extremely detailed advice on how to give the best possible performance, which at times appears to be intended for professionals, he insists that his book is accessible and for those without a teacher. Nevertheless, sheet music booklets often contained instructions for beginners too: Apollo's Cabinet provides very good information on how to play various instruments, including the flute.

Figure 4: Fingering-chart featured in Tromlitz's The Virtuoso Flute Player

Figure 4: Fingering-chart featured in Tromlitz's The Virtuoso Flute Player

Playing the flute may have been a middle-class hobby that was occasionally useful in social interactions, but it was not just perceived as that. It was not learnt purely for the knowledge of doing so, or even just for social purposes. Rather, it was supposed to have an emotional value, and be fulfilling for both the player and listeners. Burney said "there is hardly a private family in a civilised nation without its flute, its fiddle, its harpsichord, or guitar: that it alleviates labour and mitigates pain; and is still a greater blessing to humanity, when it keeps us out of mischief, or blunts the edge of care" (xxvi). On the one hand, playing an instrument was a marker of social class. Of course, you needed to have spare time to pick up music – given technical the flute, any other such instrument, or learning how to read music were. It required practice and study, yet it was also a way of relaxing after a day of hard work. The ultimate point was to feel better afterwards, and thus it allegedly had a larger spiritual purpose. Even the rather finicky Tromlitz greatly valued how people, particularly what the listener, felt whilst listening to the flute. He argues that "awaken[ing] amazement at…artistry for pure difficulty" but whilst leaving "the heart…unmoved" is not a desirable outcome (8). At the same time, he believes simple pieces are also bad, not because he thinks that music should be difficult for the sake of it, but because it will "make the listener not only indifferent but quite sleepy and yawning" (8).

Both children and adults alike picked up the flute (Tromlitz 15). Similar to the present day, parents could encourage their children to pick up an instrument. However, it was still more common for adults to try it out than it is today.

Sheet music

The cost of sheet music was rather variable: a basic piece of music adapted from a popular song could cost 6d (just under £1.40); a collection of 12 Loeillet solos would set you back 3s 3d (just over £10). It was usually sold in booklets with collections of pieces, but this was not the only way of obtaining it, however. They were often also printed in journals such as the Gentleman's Magazine alongside poetry. This meant that accessing music in England was very easy and affordable. Not all European countries had printed music at the time: when Burney attends a concert performed by a Milanese ensemble, he notes that "all the music" they use is in "MS" or manuscript form (72) – in other words, hand-written. Therefore, the printing press in England facilitated a culture where the middle-classes did not have to search particularly hard to find music.

A lot of music available for the 'German' flute was in the form of accompaniments, or otherwise also playable on other instruments. Though composers such as Loeillet or Telemann composed suites specifically tailored for the flute, the majority of pieces available were adaptations of popular songs, such as lyrical ballads sung in assembly halls. Thompson's catalogue for pieces sung at "Theatres, Public Gardens, and All Places of Entertainment" adapted for "Harp, Harpsichord, Pianoforte, Violin, German Flute, and Guitar" gives a good overview of the type of music that could be purchased. Most of these songs were pastoral or Classical in theme, and the sheet music included the original lyrics. Therefore, for the most part, flute music that the general public could buy was not high art, but sold based on recognition and familiarity.

Even composers that we would think of as masters today cashed in on the popularity of certain songs. Below is a piece composed by Handel, possibly from around 1770, called The Melancholy Nymph, which provides both a vocal melody and an accompaniment for the flute. The original song is based on a ballad taken from Act II Scene vii John Gay's The What D'Ye Call It, a "Tragi-Comi-Pastoral Farce" written in 1715.

Figure 5: The Melancholy Nymph by Handel sheet music

It was also possible to purchase sheet music versions of songs featured in John Gay's The Beggar's Opera. These had been adapted for "harpsichord, violin, or German flute" and cost 1s 6d, or under £5 in modern currency. It is advertised at the back of books published by T. Lowndes and Partners, listed alongside the scripts for "Tragedies and Comedies" that the publishing house printed – this includes the script for The Beggar's Opera. This appears to be an early form of merchandising, where others could profit off of the success of another piece of art – and The Beggar's Opera certainly was popular. Again, this was not music that was bought for its artistic merit, but because the player was likely familiar with the songs (The Beggar's Opera itself comprised popular songs). The fact that it is advertised alongside other plays suggests that it is aimed not at serious players, but at an audience that had gone to the theatre and enjoyed the play. It is very much a phenomenon that continues today, where it is possible to purchase sheet music from popular film soundtracks arranged for classical instruments.

The pastoral

Despite its presence in concert halls, homes and other such modern spheres, the flute was frequently portrayed in pastoral paintings and images.

|

|

Figure 6: A Summer Idyll, Thomas Rowlandson, c.1810-15, Yale Centre for British Art

|

|

|

Figure 7: Fête Champêtre with a Flute Player, Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Pater, c. 1720-36, The Royal Collection

|

Not only did the flute have pastoral and Classical connotations, but it was specifically associated with rustic social gatherings, which can be seen in the two pictures shown above. Both are quite conventional of eighteenth-century visual depictions of the flute. In the first picture, there is a backdrop of a college green, yet the flock of sheep and large trees seem to suggest an idyllic scene (it's worth noting that here, the flautist is holding his instrument the wrong way round). The second depicts another rustic scene, specifically a fête champêtre or fête galante, which was popularised in England in the eighteenth-century. It is a type of painting which involves fashionable people being juxtaposed against pastoral background. The flute is very rarely the focal point of the scene, and the flautist is often pictured off to the side. In both of these depictions, none of the other figures' eyelines are directed at them, and instead they are engaged in conversation or their attention is focused elsewhere, such as on the dog in the Pater painting. In the same picture, the flautist appears to be playing to himself, apparently separated from the rest of the party. In Figure 6, the flute player almost seems cut out of the conversation between the lovers, and is pictured furthest away from them. The impression we get is that performance was not the social event itself, but instead a way of accompanying social interactions.

The association of the flute and pastoral scenes is most likely due to its representation in Classical mythology. John Hawkins addresses this in A General History… The flute was supposedly invented by Apollo (ii.211), and thus associated with revelry: apparently in "Arcadia", children "assemble[d] once in every year in the public's theatres, at the feast of Bacchus, and there dance[d] with emulation to the sound of flute" (ii.182). Furthermore, the legend of Pan probably contributed towards this image.

Literary representation

Although admittedly scant, the eighteenth-century literary depictions of flutes suggest both a continuity and departure from their representation in visual culture. Rather than being placed within a pastoral or rustic context, they are seen within a domestic or upper-class sphere. Furthermore, the other characters appear to actually be listening to the flute or accompanying it, as opposed to talking and generally ignoring its presence. At the same time, it is still an instrument associated with socialising; a way of entertaining of guests who come over. For example, in later editions of Pamela, which were published after Richardson's death, there is a scene in which a number of "noble guests" are convinced to stay longer by Mr. B because he asks them to play music together, including Mr. H playing "the German flute" (412) as well as other characters demonstrating their proficiency in other instruments. This effectively keeps them entertained, as they "had an exceedingly gay Evening" as a result of all of the different performances (412). It's suggested that without the musical entertainment, the evening would have ended "more gravely" (412).

Playing the 'German' flute is also portrayed in other novels as a way with partaking in social activity and forming a connection with others. However, in the novel Caroline, we get a contrasting depiction, where playing the flute badly is representative of social awkwardness. In the scene, the eponymous heroine has run out of ways to entertain her rather awkward guest, Captain West, as his "talents for country conversation" are not "of the first class". The character of Captain West has been in the army since the age of "fifteen", and is now 22 (49). Although he is "moderately" good at "French, fencing, and dancing", his education has been "little attended to" (49). He is therefore not well-versed in conduct, and despite his good nature lots of people laugh at his social "follies" (50). As a result, Caroline has to go through alternative forms of socialising with him beyond conversing: "She would have given him a book had she not known that he did not profess to read out aloud. Her drawings had all been looked over in the morning". Eventually, she decides that "the harpsichord" and playing music "was her next resource" (96): likely because it is a form of social activity that does not require talking. Thus, once again, music is seen as a way to socialise with guests. He attempts to accompany her with her brother's "German flute", but unsuccessfully, since he can't keep up with her "for more than a bar or two at a time" (96). His inability to play the flute properly is another facet of his awkwardness; he is educated enough to know how to play, but not so much that he can stay in sync with Caroline. The encounter ends in embarrassment, as he accidentally stumbles onto Caroline just as her brother works in. So, the difference in playing ability shows the disparity between their conduct. The scene is also a comical reversal of the idea that playing music should help social situations – what happens if someone isn't very good at playing an instrument as complex as the flute.

Primary sources:

"Life of Goldsmith". Poems by Oliver Goldsmith. G. Nicholson, 1798, https://historicaltexts.jisc.ac.uk/eccoii-1314305500

Unlike a modern introduction, it lacks any sources or references. Furthermore, the editor appears to be unknown. Still useful in that it also gives Goldsmith's own opinion on his flute-playing.

Thompson's Catalogue, 1790, https://historicaltexts.jisc.ac.uk/ecco-1256400500

Gives a good idea of the type of sheet music that was popular, as well as prices.

The Royal Magazine or Gentleman's Monthly Companion, 1763, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/4XFPE0

Shows that sheet music was printed elsewhere, other than in book format.

The Old Bailey,

https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t17740112-54&div=t17740112-54&terms=flute#highlight

One of several cases which indicates the price of a flute.

The New English Theatre Vol. VIII. 1776, https://historicaltexts.jisc.ac.uk/eccoii-1346400200

It's worthing that this isn't the only text on Historical Texts where sheet music for The Beggar's Opera is advertised; all appear to be from the same publisher. Really fortunate, since it gave me another link to a text on the module.

Charles [?]. Apollo's Cabinet. John Sadler, 1757 https://historicaltexts.jisc.ac.uk/ecco-1081100901

Really rather impressed with just how detailed the instructions provided for each instrument were. Interesting in how it suggests that someone did not necessarily need to buy a separate manual and it is aimed at beginners.

Burney, Charles. The Present State of Music in Germany, the Netherlands, and United Provinces.

Extremely interesting mix of travelogue, biography, and opinion. Meets both famous musicians such as Quantz, but also locals such as a blind organist in Amsterdam. It is worth noting that Tromlitz took issue with some of the more precise details regarding flutes, but then Tromlitz might be slightly biased given his bitterness over his omission. By far the most interesting source I have encountered – would probably read both volumes at some point (the other being of France and Italy).

Flin, Lawrence. Part II. of Flin's sale catalogue of books, for the years 1767 and 1768, 1767.

Shows that Loeillet's solos cost 3s 3d

Gay, John. "The What D'Ye Call It". The Plays of John Gay: Volume 1, Chapman & Dodd, 1923.

Used for identifying the scene in which Handel's The Melancholy Nymph was taken from.

Handel, George Frideric. The Melancholy Nymph. R. Falkener, 1770?, https://historicaltexts.jisc.ac.uk/ecco-1137301600

Unhelpfully, there is no context provided for this piece: whether it was printed with other texts, how much it sold for, etc. Still a curious artefact, given the intertextual link with one of Gay's plays.

George Frideric Handel, London Early Opera. “The Melancholy Nymph” Handel at Vauxhall Volume 1, Signum Classics, 2016, Spotify, https://open.spotify.com/track/7dIXTd8wYjPfbos4J2laQW

Hawkins, John. A General History of the Science and Practice of Music. Volumes II and V, 1776/2011, Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511997525, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511997556

Unfortunately, the index is not comprehensive enough for such a large text spread over 5 volumes, which made it very difficult to search for information. Also, I'm not entirely sure how much I believe his account on Classical history, given that it does seem to be rooted in mythology. The other information provided, such as diagrams of different types of recorder, is rather detailed.

Hughes, Anne. Caroline; or, the Diversities of Fortune. Volume First, W. Lane, 1787. https://historicaltexts.jisc.ac.uk/eccoii-1607800301

Interesting because it does raise the issue of how awkward social interactions must be if one person cannot play an instrument very well. Rather annoying that only the first volume (of three) is on Historical Texts, and the full text is nigh impossible to track down, as are plot summaries. It's therefore difficult to try and fit this scene in the entire context of the novel; but if I had to hazard a guess, I would think that Caroline would end up marrying Captain West.

Mortimer, Thomas. The universal director; or, The nobleman and gentleman's true guide to the masters and professors of the liberal and polite arts and sciences; and of the mechanic arts, manufactures, and trades, established in London and Westminster, and their environs, 1763, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/4Xfpc4.

Rather useful for seeing whether or not there were teachers who exclusively taught the German flute, given that most musicians did not specialise in the instrument earlier in the century. Unfortunate that it doesn't include lists of prices.

Richardson, Samuel. Pamela or, Virtue Rewarded Vol IV. 1785, 12th edition, https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=dq4BAAAAQAAJ

I originally came across this whilst searching for 'German flute' on Historical Texts, yet became frustrated when I could not find such a mention in my own copy of Pamela. As it turns out, there were many re-editings and re-printings of Richardson's text after his death. Still a useful source for the depiction of flute playing in a social context.

Tromlitz, Johann George. The Virtuoso Flute Player. Translated and edited by Ardall Powell, Cambridge University Press, 1791/1991, doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511552427

Quite detailed and entertaining, but the opinionated and informal register makes it difficult to determine how much is his own opinion and how much is fact – especially when he briefly addresses how he was left out of Burney's journey, while Quantz was featured heavily. Nevertheless, an invaluable resource for learning about a variety of topics, from maintenance to how the flute is perceived.

Pictures:

Figure 1: Historical Texts

Figure 2: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/504019 (via Artstor)

Figure 3: www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection/search#/1/collection/72173/transverse-flute

Figure 4: (see Tromlitz)

Figure 5: (see Handel)

Figure 6: collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/1670725 (via Artstor)

Figure 7: www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection/search#/8/collection/400673/fete-champetre-with-a-flute-player

Secondary sources:

Buelow, George J. The Late Baroque Era: From the 1680s to 1740. Macmillan, 1993.

There is a very small amount of information on composers in the eighteenth-century and the configurations of chamber suites. Not particularly relevant for my page, but interesting nonetheless.

Crown, Helen. Lewis Granom: His Significance for the Flute in the Eighteenth Century. https://orca.cf.ac.uk/50783/1/THESIS.pdf

Fantastic resource that gives by far the most comprehensive overview of flute developments, teaching, and concerts throughout the century, as well as mentioning notable figures such as the Hotteterres and Quantz.

Mackerness, Eric David. A Social History of English Music. Routledge, 1964.

Gives a good amount of information of concerts in the early eighteenth-century, but not particularly helpful for specifics about the flute.

Patterson, Annabel. ‘Pastoral and Ideology: The Neoclassical “Fête Champêtre”’.

Huntington Library Quarterly vol.48 no.4, 1985, pp. 321–344,

http://www.jstor.org/stable/3817132Useful for understanding the context of the pastoral scenes, to work out how the flute fit into the rest of the paintings.

https://vsl.co.at/en/Concert_flute/History

Works well as a rough guideline to begin with. Not overly detailed, but nice overview.

oed.com

Comments (0)

You don't have permission to comment on this page.