Snuff Box

From Anita Chagar, the Warwick Undergraduate Student

A snuff box is, as defined by Samuel Johnson in 1775, "The box in which snuff is carried"[1] whilst the present day definition by the Oxford English Dictionary is "A box for holding snuff, usually small enough to be carried in the pocket".[2] Clearly not much has changed in the physical description of the object. However, what is simply viewed as a container which typically holds a powdered form of tobacco actually has a significant variety of meanings inside and outside of literature. Representations of snuff boxes show them to be products of creative freedom, signifiers of wealth and social class, indicators of gender identity and contributors to illnesses.

Using Google's Ngram Viewer[3] which graphs the usage of a word or phrase in literature, it is evident that 'snuff boxes', in all its various written forms, became popular very quickly during the last quarter of the 17th century, maintaining its vogue until the end of the 19th century. This directly correlates with the discovery and usage of snuff itself,[4] being the primary reason for the object's creation. During the 1700s, despite its widespread use, snuff boxes did not pervade the literature of the time. Despite this, accounts of the object in some literary texts make for insightful perceptions of who uses them and how they can be used. Perhaps the obscurity of the object in literature is a testament to its discrete size and nature in reality.

|

Collection of Boxes and Micromosaics, V&A Museum [Image 1]

|

History

Before a history of the snuff box can be conveyed, a brief depiction of the history of snuff must be told first. Originating in the Americas, the tobacco plant was initially used by the American Indians only to be discovered by European explorers such as Christopher Columbus and taken back to the continent for widespread use by its people. The herb was popularised during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries amongst the aristocracy, largely due to to the first royal European snuff-taker, Catherine de Medici, Queen of France, (1519-1589) who "ground the leaves to a powder and inhaled this through a tube, in the Indian method."[5]

The grinding of the tobacco leaves into a powdered form termed 'snuff' allows the herb to be inhaled up the nose in small but regular quantities. It is a stimulant due to the nicotine found in the plant, thus an addictive substance. Several flavours of snuff can be created by originally combining the powder with spices, fruit and flora, though today new flavours are manufactured such as 'Coke', 'Peanut Butter' and 'Toast and Marmalade'.[6]

The popularity of frequently taking snuff led to the need for a container to store the tobacco in. The box has to be easily accessible, kept within reach and be able to keep the snuff in good condition. As the use of snuff was so widespread across society, there were boxes appropriate and affordable to the respective user, as The Artisan Snuff Society states:[7]

"Snuff was taken from boxes that could be anything from jewelled works of art costing a fortune to buy, to small plane-wood boxes that cost a farthing or so."

Not only did the material of the boxes differ depending on the user, but the type of container snuff could be found in varied too. Several forms of the container were produced depending on the method of snuff-taking most preferable by the user. These include boxes, bottles, spoons and sticks. Many of these types of container were used for other inhalants, such as the bottle for smelling salts. As the object became increasingly prominent in the upper classes of society, the boxes became more ostentatious in their design, becoming a reflection of the social status of the owner. Since the decline in the habit of inhaling snuff, these objects can be found on display in museums or at auctions fetching large amounts of money.[8]

Snuff Box once owned by Frederick the Great of Prussia c. 1755[Image 2]

Design

The creation of snuff boxes offers the manufacturer and commissioner endless possibilities over the physical appearance of the object. Some of the stylistic choices that can be made include its shape, size, material and colour. Many boxes even include a portrait miniature on the top of and inside the lid of the box. The amount of work that goes into creating snuff boxes is alluded to in The Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection at London's Victoria and Albert Museum (often abbreviated as the V&A):[9]

"A specialist industry grew up, combining the talents of the designers, chasers, enamellers, stone-cutters and engine-turners"

The large number of people who worked on a single snuff box is reflected in the multitude of unique designs of the object. Such creative freedom has produced a myriad of snuff boxes that can still be viewed today. For example, those on display at the V&A show a range of boxes from the European aristocracy of the eighteenth century, a large communal snuff box that has been in use since the 1700s can be found in the Houses of Parliament (8),[10][11] and Mary Wollstonecraft also provides an example of a type of box for snuff in her Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark (1796):[12]

"my host, who, asking for a pinch of snuff, was presented with a box, out of which an artificial mouse, fastened to the bottom, sprang" (10)

Snuff boxes were, by and large, used by the upper social classes, including many members of royal families and heads of state,[13] allowing them to exhibit their wealth and sophistication as well as maintain their snuff-taking habits. One particular prolific user of snuff was Queen Charlotte of Great Britain and Ireland (1744-1818) whose excessive use of the substance gave her the name 'Snuffy Charlotte' [14] The popularity of snuff amongst the aristocracy meant that the boxes which contained the powdered tobacco were constantly in the public eye, some even being wore as items of jewellery.[15] Thus giving reason for the objects to be supremely ornamented with precious metals and stones, in turn becoming the objects of thievery.

Snuff Box made of tortoise shell and gold, with an ivory miniature of

Snuff Box made of tortoise shell and gold, with an ivory miniature of

Queen Charlotte of Great Britain and Ireland, c. 1761[Image 3]

As can be seen from the image above, portrait miniatures were a popular design found on the lid of snuff boxes, and sometimes on the inside of the lid too. Being personal items, the portraits featured on snuff boxes tended to be of someone important to the owner of the box, usually a family member. However, portraits of royals and other well known people of society can be found on the objects too. And more of these types of snuff boxes are being discovered all the time, for example, there has been a recent recovery of a box that features an image of who has now been identified as the composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.[16] Following on from the description of snuff box provided by Wollstonecraft, other styles of boxes became increasingly popular during the eighteenth century, including the musical snuff box. Many that were produced were constructed with a mechanism to play music when a button is pressed or wound,[17]thus providing a source of entertainment for the user. The popularity of such a type of box is most likely the inspiration for a nineteenth century piano piece of music by Anatoly Lyadov entitled "Musical Snuff-Box, Op.32 'Valse-Badinage.'"[18] A comparison can be made between the two types of music here:

Musical Snuff Box stocked and sold by Douglas Fisher[Video 1]

Anatoly Lyadov's "Musical Snuff-Box, Op.32 'Valse-Badinage'" (1893)[Video 2]

Criminality

The value of snuff boxes is evidently high, especially those used by the upper classes. Their worth is an appealing feature of the object, risking theft if they are not safely kept. There have been several documented cases of snuff boxes being stolen, which Samuel Richardson refers to in his novel Pamela (1740):[19]

"I have had a sore misfortune in going from you. When I had got as near the town as the dam, and was going to cross the wooden bridge, two fellows got hold of me, and swore bitterly they would kill me, if I did not give them what I had. They rummaged my pockets, and took from me my snuff-box, my seal-ring, and half a guinea, and some silver, and halfpence; also my handkerchief, and two or three letters I had in my pockets. By good fortune, the letter Mrs. Pamela gave me was in my bosom, and so that escaped but they bruised my head and face, and cursing me for having no more money, tipped me into the dam, crying, be there, parson, till to-morrow! My shins and knees were bruised much in the fall against one of the stumps; and I had like to have been suffocated in water and mud. To be sure, I shan't be able to stir out this day or two: for I am a frightful spectacle!" (150)

Mr Williams' experience of being robbed highlights the importance placed upon snuff boxes. It is the first item he lists as being stolen from his pockets by the rubbers, suggesting that his most valuable possession, besides Mrs. Pamela's letter, is the box. It is left to the reader to determine the physical aspects of the object in order to have an idea of it's actual worth. Being a chaplain, Mr Williams' is not wealthy enough to have a diamond-encrusted snuff box like royalty do, but that his box was still stolen by robbers alongside other items of worth - jewellery and money - goes to show that even the lesser-endowed snuff boxes were attractive enough to be embezzled.

Whilst Richardson clearly describes the extent thieves go to steal a snuff box, The Ordinary of Newgate's Accounts[20] conveys how far the justice system of the eighteenth century went to prosecute such criminals.

Images of the original Ordinary of Newgate's account of the behaviour, confessions, and last speeches of the malefactors that were executed at Tyburn in 1715[Image 4][Image 5]

The circumstances of one particular criminal, Daniel Blunt, who was accused of stealing a snuff box is described below:

"Daniel Blunt, alias Rider, (the former being his right Name) condemn'd for picking Mr. Joseph Greenway's Pocket of a Silver-Snuffbox, on the 28th of September last. He said, he was 27 Years of age, born in Little Grays-Inn-lane, in the Parish of St. Andrew, Holborn: That he serv'd Ten Years at Sea , viz. Five in the Royal Navy, on board the Greenwich, the Boyne, the Experiment, Rochester, and two or three Men of War besides; and the other Five Years in Merchantmen: That he was not guilty of this Fact, but seeing that Snuffbox on the Ground, he took it up and put it into his own Pocket: and, That he never robb'd any Person of any thing in his Life, only his own Mother, when he was a Boy: But I shew'd him he did not speak the Truth in that, for I knew he had before this, viz. in September 1714, been convicted of a Felony for stealing an Handkerchief, and was whipt for it, and since that had committed some Robberies on the Highway: Then he confess'd it was so; and, That about 7 or 8 Months ago he was enticed by some Highway-men to go along with them, and in their Company committed 6 or 7 Robberies on the Highway, whereby he got no great matters; but being taken at last, should have suffer'd the Punishment he deserv'd, had he not obtain'd his Pardon by becoming an Evidence against two of them, viz. John Kennady and Peter Wells, who did, both of 'em, receive Sentence of Death at the late Assizes at Maidstone in Kent, and accordingly were executed there"[21]

This account provides several examples of indicators that a snuff box is of great value, and how far a person would go to have it for himself. In the first instance, that Blunt is on trial for being accused of stealing a snuff box demonstrates that such an action is a serious crime, and that Greenway's choice to condemn Blunt for the action rather than let it subside highlights the importance of the snuff box to Greenway. It is also difficult to neglect the fact that Blunt is on trial for execution for his crimes. Analysing Blunt's defence, his supposed action of picking up a snuff box from the ground and pocketing it implies that such an object does not go unnoticed or unwanted. If Blunt's defence was the truth, but the object in question was, perhaps, a linen bag[22] he saw on the ground rather than a snuff box, would Blunt have picked it up? In a modern sense, a snuff box could be likened to a mobile phone or an iPod, so you could ask yourself the same question: What would you pick up from the ground, a phone or a plastic bag?

Masculinity and Femininity

Nicolas Kugel, co-owner of a gallery in Paris which exhibits snuff boxes, states that

“The snuffbox, essentially a masculine object, was a container for tobacco that the user would take to his nose in order to sneeze”[23]

Though not explicitly mentioned, the use of a snuff box is implied in a line from Laurence Sterne's The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759-67):[24]

"not passing by a woman in a mulberry-tree without commending her legs, and tempting her into conversation with a pinch of snuff" (484)

The narrator implies that the snuff box does more than just satisfy its owner's snuff-taking habits by containing a measure of the powdered tobacco - it can be used to woo a lady too. From this description, Kugel comments on the obejct being a highly masculine object is demonstrated, the box giving Tristram an excuse to maintain a flirtatious interaction with a woman. However, other literature suggests that snuff boxes can not only be used to the advantage of men, but can be a tool for feminine power too. The use of a snuff box in Alexander Pope's The Rape of the Lock (1717)[25] introduces the object as conforming to the common perception of it being a representation of masculinity, but then subverts this by the end of the poem. The first time a snuff box is featured, it is in the hands of a man, Sir Plume who uses it when faced with the rage of a woman:

She said; then raging to Sir Plume repairs,

And bids her Beau demand the precious hairs:

(Sir Plume, of amber Snuff-box justly vain,

And the nice conduct of a clouded Cane)

With earnest Eyes, and round unthinking Face,

He first the snuff-box open'd, then the case,

And thus broke out — "My Lord, why, what the Devil?

"Z—ds! damn the Lock! 'fore Gad, you must be civil!

"Plague on't! 'tis past a jest — nay prithee, pox!

"Give her the hair — he spoke, and rapp'd his box. (4. 121-130)

Sir Plume uses the snuff box to create a barrier between himself and Thalestris, initially taking out and opening the box before speaking. This pause can be construed as hesitancy which contrasts with Sterne's portrayal of Tristram's confidence around women. Sir Plume's fragmented speech emphasises this lack of assertion, and the rap on the box at the close of his dialogue acts as an attempt to make up for the determined tone his words lack. When looked upon closely, a snuff box can be seen in the hands of Sir Plume in C. R. Leslie's painting of this scene [Image 6]. The artist captures the shift in authority from male to female through the images of Sir Plume and Thalestris. The man, who can be found on the left of the painting looking at the lock of hair held up in front of the window with snuff box in hand, is turned away from the ladies, as if reluctant to witness the emotional scene behind him and acknowledge the right for revenge Thalestris seeks on behalf of Belinda. Moreover, Thalestris can be seen sitting down in the centre of the painting, looking towards the group of men with a whip in hand with a determined look upon her face.

C.R. Leslie, 'Sir Plume Demands the Restoration of the Lock' (1814), oil[Image 6]

What is held in the hands of this couple is immediately telling of the exchange that is to follow: the riding whip is currently a weapon in a woman's intended to be used on the men, whilst the snuff box is open and resting in the hand of a man lacking authoritative control upon the event, yet when the snuff box is eventually found in a woman's hand, it is transformed into a weapon used for revenge. The next time snuff is mentioned in the poem, it is in the hands of Belinda, who uses the substance to overwhelm the Baron:

But this bold Lord, with manly Strength indu'd,

She with one Finger and a Thumb subdu'd,

Just where the Breath of Life his Nostrils drew,

A Charge of Snuff the wily Virgin threw (5.79-82)

Pope initially creates the impression that the Baron is strongly masculine, describing him as "with manly Strength inbu'd." But the poet is quick to undermine the character through Belinda's actions in the following line, suggesting that with minimal effort and "one Finger and a Thumb" she is able to attack the Baron. The rhyming couplet used by Pope emphasises the conflict between the sexes, as the likeness of the words suggest that a sense of equality which correlates with Belinda seeking her 'getting her own back', yet the meaning of the words shows that there is a significant imbalance between the couple. This disproportion between Belinda and the Baron is the central focus of an engraving of this scene by C.P. Marillier and L. Halbou [Image 7]:

C.P. Marillier and L. Halbou, Canto V of 'La Boucle de cheveux enlevèe' (1799), engraving[Image 7]

In the foreground of the engraving, the Baron is seen sprawled on the floor whilst Belinda stands above him, her figure dominating the scene. The positioning of the characters is indicative of the inferiority of the former and superiority of the latter. Belinda is holding out the snuff box, displaying her weapon of choice almost patronisingly, and the Baron raises his arm against it, likening the motion to an intrinsic act of defence against an oncoming attack. Feminine supremacy through the use of a snuff box is displayed here bluntly.

Sterne Snuff

A snuff box features prominently in Laurence Sterne's A Sentimental Journey (1768).[26] The scene it is present in incorporates several aspects to the object already mentioned, such as its design and its relationship to masculinity and femininity. The narrator, Yorick draws attention to the style of his own snuff box in comparison to the monk's by describing the material each is made up of. The monk's is "a horn snuff-box" (20) whilst his own is "a small tortoise one" (21). The materials are indicative of the social status of both characters, with tortoise-shell being a significantly more expensive material than horn,[27] thus implying the wealth and higher status of Yorick over the monk. Because of this circumstance, the interaction that takes place between the men supports the choice of the word 'Sentimental' to be used in the title of the text:

"do me the favour, I replied, to accept of the box and all, and when you take a pinch out of it, sometimes recollect it was the peace-offering of a man who once used you unkindly, but not from his heart... be it as it would - he begg'd we might exchange boxes - In saying this, he presented his to me with one hand, as he took mine from me in the other; and having kiss'd it - with a stream of good nature in his eyes he put it into his bosom - and took his leave. I guard this box... I seldom go abroad without it" (21)

It is the extensive dedication of words to the exchange of snuff boxes that signifies the importance of the action, and the response by the men to this moment heightens the sentimentality of the exchange. Terming it as a "favour" and a "peace-offering" makes the scene an endearing one, whilst the warm behaviour by both men towards the object, "having kiss'd it" and guarding it closely contrasts with the much more cool and withdrawn attitude towards snuff boxes displayed in other literary texts such as Pamela and Tristram Shandy, where they are purely commodities as objects of thievery and flirtation. Instead, both Yorick and the monk place their affections for each other upon the box, transforming it into an object of sentiment, as Lynn Festa states in Sentimental Figures of Empire in Eighteenth Century Britain and France (2006):[28]

"By inviting us to have feelings about things - to love them - the sentimental seduces us into taking object for subject; by packaging feelings in a commodity form" (69)

This alternative display of masculinity resembles an eighteenth century interaction that has been viewed as more feminine in nature: the exchange of friendship boxes. Originally specific oval-shaped boxes were presented as gifts from one female to another, but eventually other boxes, including snuff boxes, were used too. Elizabeth Eger's analysis of the letters exchanged between Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Portland, illustrator Mary Delany and critic Elizabeth Montagu[29]proves that such friendships existed, where an object became a symbolic representation of the connection between two or more people. These friendships continued even after death, as the Duchess gave out snuff boxes to her closest companions in her will, in a similar way to Yorick's withholding of the monk's snuff box even after finding out about his death and visiting his grave (22). Thus, Eger's comments on the sentimental importance of such objects rings true:

"Objects thus take on an endowed significance beyond the lifetime of their original owners, extending and embodying human relationships in defiance of mortality"

Snuff beside a Snuff Box[Image 8]

Medical

The vogue for snuff boxes reflects the prevalence of snuff itself. Yet there was an increasing concern for the effects of using so snuff so frequently, with one gentleman actually writing a letter to a magazine expressing his concerns:[30]

"Though these queries relate merely to private doubts, the subject of them affects too large a proportion of our fellow-creatures to be altogether overlooked. I am, therefore, anxious to learn, whether, though snuff is a present gratification, the habitual use of it is not materially injurious to health and longevity?"

The gentleman had good reason to be concerned, as a study into snuff-taking conducted in the nineteenth century detailed just how often a typical snuff-taker used the substance:

Image of essay summary on snuff feature in The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction[Image 9]

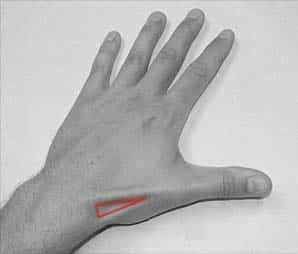

Alongside the fact that the substance contains nicotine, an addictive drug found within tobacco, the ease of which you can take snuff heightens the fear of the consequences of the habit. There are two common ways of taking snuff, one is the popular 'Finger and Thumb' method as mentioned in Pope's The Rape of the Lock, where a pinch of snuff is taken directly from the snuff box to the nose and inhaled. Such a simplistic task promotes the regular conduct of it. An alternative method involves the use of the 'anatomical snuff box', located in the triangular shaped indent that is formed in your hand when your thumb is bent away from the rest of your fingers.[31]

Location of the anatomical snuff box[Image 10]

Location of the anatomical snuff box[Image 10]

Evidently, all that is needed to take snuff is the snuff itself and your hand, making it an effortless action and so an easy one to repeat. Using snuff in these ways so regularly creates concern for the damage that can be done to the nasal passages due to the force that is exerted in order to inhale the powder. An essay featured in an issue of the British Medical Journal[32] (now BMJ) refers to a study that identifies a correlation between habitual snuff-taking and a cancerous illness, 'antral carcinoma', in the Bantu peoples:[33]

"The use of indigenous snuffs is widespread among the Bantu and 80% of the patients with antral carcinoma admitted to prolonged usage of snuff"

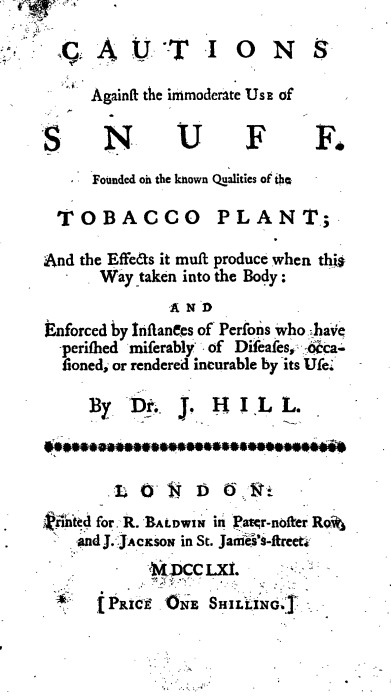

This being a twentieth century study does not mean that seventeenth century society were unaware of the risks of frequent snuff-taking. Dr John Hill published a piece documenting several examples of the severely negative effects of taking tobacco[34], describing illnesses such as diarrhoea, vertigo, fits and vomiting (4-7). He is more explicit in detailing the effects of taking snuff, describing the reaction of a first time user (9-10) and a more frequent one (10-11). He warns of the loss of smell as the nerves in the nostrils are eventually destroyed by the substance, and goes on to explain how snuff can also affect the stomach, travelling down the throat from the nose to get there (12-16). Hill applies these affects to everyday scenarios to illustrate the extent to which taking snuff can have consequences upon. For example, a man being unable to smell the bunch of flowers he gives a woman (17-18), or the Portuguese who make wine without being able to smell the differences amongst them (21-23). His advice on combating the addiction is to simply throw away the snuff box (56) or wean yourself off of it by placing something distasteful within the snuff (57), but Hill ultimately advises that the cure is "more in the mind than the medicine" (57).

Front page of Dr John Hill's essay on the cautions of snuff[Image 11]

Front page of Dr John Hill's essay on the cautions of snuff[Image 11]

Being an addictive stimulant, snuff can be compared to coffee, which also rose in popularity during the eighteenth century. An article in The Glasgow Herald from 1951[35] compares the two substances through the places they were often taken: coffee-houses that doubled as snuff-houses too. Incidentally, the piece quotes the words of eighteenth century French diplomat Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord which can be likened to the depiction of Sir Plume in Pope's poem and the monk in Sterne's A Sentimental Journey, suggesting that snuff and snuff boxes provide a rather comical excuse to pause and adapt to a surprising situation:

"the opening of his snuffbox and the taking of pinch allowed him time to think out an answer to an awkward question of conceal his reaction to an adversary’s statement”

That 'Snuff of That!

Watch Stephen Fry and the QI team for a humorous but nevertheless informative example of the different flavours of snuff, how it should (and should not) be taken, the (slightly off-putting) need for a snuff handkerchief, and the benefits of taking snuff:

Stephen Fry's guests take snuff on QI[Video 3]

References

1. ^ http://johnsonsdictionaryonline.com/?page_id=7070&i=1871

2. ^ "ˈsnuff-box, n.". OED Online. December 2013. Oxford University Press. 18 February 2014 <http://0-www.oed.com.pugwash.lib.warwick.ac.uk/view/Entry/183571>.

3. ^ https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=snuff-box%2csnuffbox&case_insensitive=on&year_start=1600&year_end=2000&corpus=15&smoothing=10&share=&direct_url=t4%3b%2csnuff%20-%20box%3b%2cc0%3b%2cs0%3b%3bsnuff%20-%20box%3b%2cc0%3b%3bSnuff%20-%20box%3b%2cc0%3b%3bSnuff%20-%20Box%3b%2cc0%3b.t4%3b%2csnuffbox%3b%2cc0%3b%2cs0%3b%3bsnuffbox%3b%2cc0%3b%3bSnuffbox%3b%2cc0%3b%3bSnuffBox%3b%2cc0

4. ^ https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=snuff&year_start=1600&year_end=2000&corpus=15&smoothing=10&share=&direct_url=t1%3B%2Csnuff%3B%2Cc0

5. ^ http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2507&dat=19510830&id=vzY1AAAAIBAJ&sjid=OaYLAAAAIBAJ&pg=3972,4825763

6. ^ http://www.toquesnuff.com/gbu0-display/splash.html

7. ^ http://theartisansnuffsociety.com/history/

8. ^ http://www.bonhams.com/auctions/19483/

9. ^ http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/t/the-rosalinde-and-arthur-gilbert-collection/

10. ^ http://www.parliament.uk/documents/commons-information-office/g07.pdf

11. ^ https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/snuff?unfold=1

12. ^ Wollstonecraft, Mary. Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark. Ed. Tone Brekke and Jon Mee. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2009. Print.

13. ^ http://www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection-search/snuffbox?f[0]=im_field_object_types%3A891

14. ^ http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2507&dat=19510830&id=vzY1AAAAIBAJ&sjid=OaYLAAAAIBAJ&pg=3972,4825763

15. ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/550707/snuffbox

16. ^ http://www.thehistoryblog.com/archives/22774

17. ^ http://www.douglas-fisher.com/index.php?pg=stock&cat=singing_bird&stock=58

18. ^ http://www.classicalarchives.com/work/372594.html#tvf=tracks&tv=about

19. ^ Richardson, Samuel. Pamela, Or, Virtue Rewarded. E.d. Tom Keymer, and Alice Wakely. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2001. Print.

20. ^ http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/static/Ordinarys-accounts.jsp

21. ^ http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=OA17151102&div=OA17151102&terms=Snuffbox#highlight

22. ^ http://woodsrunnersdiary.blogspot.co.uk/2012/03/thoughts-on-18th-century-food-packaging.html

23. ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/22/fashion/22iht-acag-box22.html?_r=0

24. ^ Sterne, Laurence. The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. E.d Melvyn New, and Joan New. London: Penguin Books, 2003. Print.

25. ^ Pope, Alexander. "The Rape of the Lock". Eighteenth Century Poetry: An Annotated Anthology. Ed. David Fairer and Christine Gerrard. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub. 2004. 113-132. Print.

26. ^ Sterne, Laurence. A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy by Mr. Yorick. London: Penguin Books, 2001. Print.

27. ^ <http://www.ebay.co.uk/gds/TORTOISESHELL-Real-or-fake-How-to-tell-the-difference-/10000000012067858/g.html>

28. ^ Festa, Lynn M. Sentimental Figures of Empire in Eighteenth-Century Britain and France. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006. Print.

29. ^ Elizabeth Eger. "Paper Trails and Eloquent Objects: Bluestocking friendship and material culture." Parergon 26.2 (2009): 109-138. Project MUSE. Web. 22 Feb. 2014.<http://0-muse.jhu.edu.pugwash.lib.warwick.ac.uk/journals/parergon/v026/26.2.eger.html>

30. ^ DUBITATOR. "Letter." The Gentleman's Magazine: and historical chronicle. 45 (1775): 174. ProQuest. Web. 22 Feb. 2014.

<http://0-search.proquest.com.pugwash.lib.warwick.ac.uk/docview/8557981/747E14A4D79645C8PQ/1?accountid=14888>

31. ^ http://teachmeanatomy.info/upper-limb/areas/anatomical-snuffbox/

32. ^ http://www.bmj.com/

33. ^ http://www.jstor.org/stable/25401535?seq=2&Search=yes&searchText=abuses&searchText=snuff&searchText=its&searchText=and&list=hide&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dsnuff%2Band%2Bits%2Babuses%26amp%3Bacc%3Don%26amp%3Bwc%3Don%26amp%3Bfc%3Doff&prevSearch=&resultsServiceName=null

34. ^ Hill, John. "Cautions against the immoderate use of snuff. Founded on the known qualities of the tobacco plant; And the Effects it must produce when this Way taken into the Body: and enforced by instances of persons who have perished miserably of diseases, occasioned, or rendered incurable by its use." N.p. (1761). Eighteenth Century Collections Online. Web. 22 Feb. 2014

<http://find.galegroup.com/ecco/retrieve.do?scale=0.33&sort=Author&docLevel=FASCIMILE&prodId=ECCO&tabID=T001&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&searchType=BasicSearchForm&qrySerId=Locale%28en%2C%2C%29%3AFQE%3D%280X%2CNone%2C100%29Cautions+against+the+immoderate+use+of+snuff.+Founded+on+the+known+qualities+of+the+tobacco+plant%3B+A%3AAnd%3ALQE%3D%28BA%2CNone%2C124%292NEF+Or+0LRH+Or+2NEK+Or+0LRL+Or+2NEI+Or+0LRI+Or+2NEJ+Or+0LRK+Or+2NEG+Or+0LRF+Or+2NEH+Or+0LRJ+Or+2NEM+Or+0LRN+Or+2NEL+Or+0LRM%24&retrieveFormat=MULTIPAGE_DOCUMENT&inPS=true&userGroupName=warwick&docId=CW3307529173¤tPosition=4&workId=0274900700&relevancePageBatch=CW107529116&contentSet=ECCOArticles&callistoContentSet=ECCOArticles&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&reformatPage=N&retrieveFormat=MULTIPAGE_DOCUMENT&scale=0.33&orientation=&lastPageIndex=58&showLOI=&quickSearchTerm=box&stwFuzzy=None&searchId=R1&pageNumber=1>

35. ^ <http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2507&dat=19510830&id=vzY1AAAAIBAJ&sjid=OaYLAAAAIBAJ&pg=3972,4825763>

Annotated Bibliography

PRIMARY SOURCES

Wollstonecraft, Mary. Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark. Ed. Tone Brekke and Jon Mee. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2009. Print.

Documenting her experiences abroad, Wollstonecraft conveniently describes the design of a snuff box she sees whilst in Sweden, which has become a useful literary example of the varying styles of boxes that can be produced. The text as a whole has a limited number of snuff box references, but that was expected as the object is not the focal point of her letters.

Richardson, Samuel. Pamela, Or, Virtue Rewarded. E.d. Tom Keymer and Alice Wakely. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2001. Print.

An epistolary novel revolving around a young girl's attempts to maintain her dignity in the face of male lust, Richardson's work provides a depiction of a robbery that includes the theft of a snuff box. This description helped introduce the section on criminality and snuff boxes, as I was able to give a close reading to a fictional account comparison to a realistic one.

Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.0, 19 February 2014), Ordinary of Newgate's Account, November 1715 (OA17151102).<http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=OA17151102&div=OA17151102&terms=Snuffbox#highlight>

Digitised copies of accounts of trials at the Old Bailey from 1674-1913, several cases of snuff boxes being stolen have been documented. This one in particular portrays the criminal background of the accused, Daniel Blunt, and his argument in defence of his arrest. It has proven to be an insightful account as it also demonstrates the views of the justice system on the theft of objects such as snuff boxes, executing those who steal them.

Sterne, Laurence. The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. E.d Melvyn New, and Joan New. London: Penguin Books, 2003. Print.

A rather confusing text, is my personal opinion of this novel that attempts to narrate the life of Tristram Shandy, but ends up becoming an extensive ramble about several aspects of his life. Otherwise, it provides an intriguing demonstration of how a snuff box can be used as part of a man's attempt to woo a lady, supporting the view that snuff boxes are a largely masculine object.

Pope, Alexander. "The Rape of the Lock". Eighteenth Century Poetry: An Annotated Anthology. E. d. David Fairer and Christine Gerrard. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub. 2004. 113-132. Print.

Pope's epic poem is the consequence and reflection of a true circumstance that took place amongst people of the higher social class. I found the poet's transformation of a snuff box into a weapon used by women to seek revenge against men surprising but pleasing because of the balance between the sexes it creates. The paintings that depict the scenes in the poem allowed me to write an enlightening close reading cross-referencing both sources.

Sterne, Laurence. A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy by Mr. Yorick. London: Penguin Books, 2001. Print.

Sterne has a habit of confusing me greatly, yet I enjoyed reading Yorick's documentation of his travels in Europe, as I could draw comparisons to Wollstonecraft's own accounts as separate from snuff boxes. Yet, the chapter dedicated to the snuff box exchange became an emotional literary description, especially in light of Lynn Festa's analysis of the text and the information about female friendship boxes.

DUBITATOR. "Letter." The Gentleman's Magazine: and historical chronicle. 45 (1775): 174. ProQuest. Web. 22 Feb. 2014.

<http://0-search.proquest.com.pugwash.lib.warwick.ac.uk/docview/8557981/747E14A4D79645C8PQ/1?accountid=14888>

This letter, featured in The Gentleman's Magazine, gives a direct view of public opinion towards snuff. Though not representative of all society, the writer's concerns are valid and justified by other documents produced in the eighteenth century and raise questions that you can relate to in today's world regarding other addictive substances.

Hill, John. "Cautions against the immoderate use of snuff. Founded on the known qualities of the tobacco plant; And the Effects it must produce when this Way taken into the Body: and enforced by instances of persons who have perished miserably of diseases, occasioned, or rendered incurable by its use." N.p. (1761). Eighteenth Century Collections Online. Web. 22 Feb. 2014

<http://find.galegroup.com/ecco/retrieve.do?scale=0.33&sort=Author&docLevel=FASCIMILE&prodId=ECCO&tabID=T001&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&searchType=BasicSearchForm&qrySerId=Locale%28en%2C%2C%29%3AFQE%3D%280X%2CNone%2C100%29Cautions+against+the+immoderate+use+of+snuff.+Founded+on+the+known+qualities+of+the+tobacco+plant%3B+A%3AAnd%3ALQE%3D%28BA%2CNone%2C124%292NEF+Or+0LRH+Or+2NEK+Or+0LRL+Or+2NEI+Or+0LRI+Or+2NEJ+Or+0LRK+Or+2NEG+Or+0LRF+Or+2NEH+Or+0LRJ+Or+2NEM+Or+0LRN+Or+2NEL+Or+0LRM%24&retrieveFormat=MULTIPAGE_DOCUMENT&inPS=true&userGroupName=warwick&docId=CW3307529173¤tPosition=4&workId=0274900700&relevancePageBatch=CW107529116&contentSet=ECCOArticles&callistoContentSet=ECCOArticles&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&reformatPage=N&retrieveFormat=MULTIPAGE_DOCUMENT&scale=0.33&orientation=&lastPageIndex=58&showLOI=&quickSearchTerm=box&stwFuzzy=None&searchId=R1&pageNumber=1>

Dr Hill's detailed essay brings attention to the consequences of frequently taking snuff, both warning and advising readers to be wary of the affects and how to prevent them or cure them. I especially liked the examples the essayist provides to illustrate scenarios where snuff impacts negatively upon the user. In corroboration with the letter from The Gentleman's Magazine, I was able to create a kind of discourse amongst eighteenth century writing on snuff.

SECONDARY SOURCES

Halsband, Robert. The Rape of the Lock and Its Illustrations, 1714-1896. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980. Print.

An extremely useful text that directed me to the painting and engraving featured in the Wiki-page. Halsband discusses the various artistic depictions of scenes from Pope's Rape of the Lock to create a invaluable collection of such work. That snuff boxes are actually featured in some of them influenced the decision to dedicate a significant amount of the 'Masculinity and Femininity' section towards analysis of the images.

Festa, Lynn M. Sentimental Figures of Empire in Eighteenth-Century Britain and France. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006. Print.

An extensive analysis of objects and humans in the eighteenth century in relation to affection and nostalgia, Festa sheds light on the snuff box scene in Sterne's A Sentimental Journey, which helped me create a connection between the text and the letters of the Duchess of Portland, Mary Delany and Elizabeth Montague.

Elizabeth Eger. "Paper Trails and Eloquent Objects: Bluestocking friendship and material culture." Parergon 26.2 (2009): 109-138. Project MUSE. Web. 22 Feb. 2014.<http://0-muse.jhu.edu.pugwash.lib.warwick.ac.uk/journals/parergon/v026/26.2.eger.html>

It was fascinating to read this essay on the objects that featured within friendships and the importance they held in them. Discovering that snuff boxes were given as gifts and put into wills made me realise just how highly regarded these objects were in eighteenth century society, which I feel supports the view that regular snuff-taking is directly correlated to the popularity of the containers in which the substance is found.

Harrison, D.F.N. "Snuff: Its Use and Abuse." The British Medical Journal 2. 5425 (26 Dec. 1964): 1649-1651. JSTOR. Web. 22 Feb. 2014.

<http://www.jstor.org/stable/25401535?seq=2&Search=yes&searchText=abuses&searchText=snuff&searchText=its&searchText=and&list=hide&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dsnuff%2Band%2Bits%2Babuses%26amp%3Bacc%3Don%26amp%3Bwc%3Don%26amp%3Bfc%3Doff&prevSearch=&resultsServiceName=null>

This essay on the details of snuff, including how to prepare to take it and the effects it has upon the users, was a difficult read because of its scientific language and analysis. However, it gives a useful comparison to the way in which snuff was spoken about in medical terms between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries, and helps the reader to understand the consequences of taking snuff through more recent references.

Tea in a Teacup. "Snuff Medicinally Considered: History Repeating Itself?" Wordpress.com. Wordpress.com, 12 Jun. 2011. Web. 22 Feb 2014.

<http://teainateacup.wordpress.com/2011/06/12/snuff-medicinally-considered-history-repeating-itself/>

This blog post by an anonymous writer was helpful because it directed me to other articles and sources of information to be used in my 'Medical' section. An enjoyable read because it is clear and concise, it was also nice to see a recent publication on snuff posted online for pure enjoyment.

Images

1. ^ Collection of Boxes and Micromosaics from The Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection. N.d. Photograph. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Victoria and Albert Museum. Web. 19 Feb. 2014.

<http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/galleries/level-3/room-72-boxes-micromosaics/>

2. ^ Oval green snuffbox once owned by Frederick the Great of Prussia, about 1755. N.d. Photograph. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Victoria and Albert Museum. Web. 22 Feb. 2014.

<http://www.vam.ac.uk/users/node/6032>

3. ^ Snuff box incorporating a miniature of Queen Charlotte when Princess Sophia Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. 2012. Photograph. The Royal Collection, London. The Royal Collection. Web. 19 Feb. 2014.

<http://www.royalcollection.org.uk/eGallery/object.asp?category=288&object=43892&row=10&detail=about>

4. ^ Image of page four of the original Ordinary of NEWGATE HIS ACCOUNT OF The Behaviour, Confessions, and Last Speeches of the Malefactors that were Executed at TYBURN on Wednesday the 2d of November, 1715. N.d. Photograph. Guildhall Library, London. The Proceedings of the Old Bailey. Web. 19 Feb. 2014.

<http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/images.jsp?doc=OA171511020004>

5. ^ Image of page five of the original Ordinary of NEWGATE HIS ACCOUNT OF The Behaviour, Confessions, and Last Speeches of the Malefactors that were Executed at TYBURN on Wednesday the 2d of November, 1715. N.d. Photograph. Guildhall Library, London. The Proceedings of the Old Bailey. Web. 19 Feb. 2014.

<http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/images.jsp?doc=OA171511020005>

6. ^ Leslie, C.R. Sir Plume Demands the Restoration of the Lock. 1814. Photograph. Madame Gilflurt. Pinterest. Web. 20 Feb. 2014.

<http://www.pinterest.com/pin/531987774702947579/>

7. ^ Marillier, C. P. and L. Halbou. Canto V of 'La Boucle de cheveux enlevèe'. 1779. Photograph. Pottier Library, Paris. Librarie Pottier. Web. 20 Feb. 2014.

<http://www.livre-rare-book.com/displayImage/LPS/000121_4.jpg>

8. ^ gitanna. Detail of a pinch of snuff to pipe smoking. N.d. Photograph. 123RF Stock Photos. 123RF. Web. 23 Feb. 2014.

<http://www.123rf.com/photo_17043289_detail-of-a-pinch-of-snuff-to-pipe-smoking.html>

9. ^ Image of summary of an essay on snuff-taking from The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction, Volume 2. 2009. Photograph. University of California, California. Google Books. Web. 23 Feb. 2014.

<http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=FU0YAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA309&lpg=PA309&dq=snuff+box+1700s+literature&source=bl&ots=Mi3jIaGYA7&sig=TO9Lyb-HpGOacnjAivBhvWYVj08&hl=en&sa=X&ei=3tbeUoSNGInm7Ab88IGwDg&ved=0CEQQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q&f=false>

10. ^ Fig 1.0 – The left anatomical snuffbox. N.d. Photograph. Oliver Jones. TeachMeAnatomy. Web. 23 Feb. 2014.

<http://teachmeanatomy.info/upper-limb/areas/anatomical-snuffbox/>

11. ^ Image of the front page of Dr John Hill's essay on the cautions of snuff. 2003. Photograph. British Library, London. Eighteenth Century Collections Online. Web. 23 Feb 2014.

<http://callisto.ggsrv.com/imgsrv/FastFetch/$DHGRY68;A%3FE=%3EF@ABCDFFV4%7C%7B0*ZNMSTH2%3C@%3C1Ef=D%3CS;9Rngf>

Videos

1. ^ Fisher, Douglas. "Musical snuffbox, with hidden erotic pictorial enamel of Venus Urbino." Online video clip. Youtube. Youtube, 27 Feb. 2013. Web. 22 Feb. 2014. <http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=zKLDSfCywek>

2. ^ Pavlov, Sergei. "Liadov. Musical Snuff Box with Sergei Pavlov." Online video clip. Youtube. Youtube, 27 Mar. 2008. Web. 22 Feb 2014.

<http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VVfyiDO7Kk0>

3. ^ BBC. 2Stephen Fry's guests take snuff - QI: Series K Episode 2 Preview - BBC Two." Online video clip. Youtube. Youtube, 10 Sept. 2013. Web. 22 Feb 2014.

<http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ri6Y-cXACqM>

Comments (0)

You don't have permission to comment on this page.